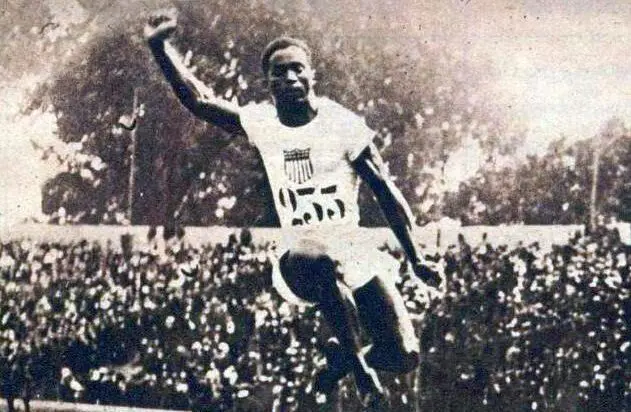

A century ago, at a small stadium just outside Paris, a college track and field star from Ohio named William DeHart Hubbard took a dramatic leap forward for himself and for all African Americans back home in the segregated United States of America.

By defeating the best long jumpers in the world at the 1924 Paris Olympics, Hubbard became the first Black athlete to win an individual gold medal at the Games.

Hubbard’s nephew Kenneth Blackwell, the former secretary of state of Ohio, told NBC News his uncle recognized that he was carrying the hopes and dreams of millions of Black Americans on his muscular frame when he raced down a track toward a sand pit and leaped into history.

“He wrote his mother a letter that I now have framed, and the letter simply said that he was going across the ocean to become the first Negro to win an Olympic medal in track and field, to make her proud, but also to show there are no boundaries that cannot be broken,” said Blackwell, who was once mayor of Hubbard’s hometown, Cincinnati.

A copy of that letter will be on display this month at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England, at an exhibition celebrating the centennial of the 1924 Olympics.

While the language Hubbard used is slightly different from the way Blackwell described it, the point the young athlete was trying to get across is the same.

“Tell Papa I got his letter, but have been busy traveling etc., and have not had the time to answer. Tell him I’m going to do my best to be the FIRST COLORED OLYMPIC CHAMPION,” Hubbard wrote.

Hubbard underlined the uppercase words for extra emphasis.

Blackwell said his uncle also qualified to compete in the 100-meter dash and the high hurdles but was denied the chance because of racism.

“When he got here, he was told that the 100 and the high hurdle were white-only events,” he said. “He couldn’t compete. And he won the gold medal on the long jump.”

Camille Paddeu, a curator at the Musee Municipal d’Art et d’Histoire in the city of Colombes, where the main stadium for the 1924 Paris Olympics is located, told NBC News her research confirms that Hubbard was blocked from competing in other events because he was Black.

Hubbard’s victory was one of several Olympic firsts at the 1924 games, which were held in and around the City of Lights as the Roaring ’20s were underway.

Among other things, they were the first Games to be broadcast on the radio, enabling listeners around the world to experience some of the unfolding drama and glory, as well as the pageantry of the opening and closing ceremonies at the Olympic Stadium in Colombes, where Hubbard competed.

The main antenna was atop the Eiffel Tower.

They were also the first games to have an Olympic village where the athletes could stay; it even included a post office, a hair salon and a restaurant.

Fatoumata Sow, who is deputy mayor of the Paris suburb of Colombes, which is home to what was then the main Olympic stadium, told NBC News that as far as she knows the only athletes who actually stayed in the village were from Japan.

These were also the first Games to use the Olympic motto “Citius, Altius, Fortius,” which is Latin for “Faster, Higher, Stronger.”

The 50-meter pool with marked lanes made its debut at those Games and became the standard for all Olympic Games that followed.

Johnny Weissmuller, the Michael Phelps of his time, won three gold medals at the 1924 Olympics, along with a bronze for team water polo, and went on to star in a series of Tarzan movies.

Those Olympic games also hosted a marked increase in the number of female athletes. Of the 3,089 athletes who competed in Paris, 135 were women.

Still smarting from World War I, the Olympic organizers did not extend Germany an invitation to take part. But countries like Ecuador, Ireland, Lithuania and Uruguay took part for the first time.

In fact, Uruguay’s soccer team took home the gold medal.

The U.S. won 47 gold medals, the most of any country at the 1924 Games. One of them was awarded to mixed doubles tennis player Richard Norris Williams, who had survived the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

To film-going audiences, those Games may be best known as the setting for the Oscar-winning movie “Chariots of Fire.”

The 1981 film told the stories of British runner Harold Abrahams, who overcame antisemitism to win gold and silver medals, and his rival, Eric Liddell, a devout Christian who refused to run on a Sunday for religious reasons but still managed to bring home gold and bronze medals running on weekdays.

Blackwell said the producers of the movie interviewed his mother extensively.

“When we watched ‘Chariots of Fire,’ there he was, my uncle warming up in the jump pit,” Blackwell said. “My mother said, ‘Is that all there is?’”

Tassou said the 1924 Games also saw the rise of what has become an inescapable feature of the Olympics — swag.

“This is the first merchandise, you could say, from the 1924 Olympics,” she said. “Basically, they resemble dolls, and about six of them were made representing different sports.”