By William C. Rhoden

Jackson State head coach T.C. Taylor was a 10-year-old boy growing up in McComb, Mississippi, when he saw his first Jackson State football game.

Thirty-six years after that first experience, Taylor’s family and close friends watched on Saturday as the 46-year-old led Jackson State to its first Celebration Bowl victory. Jackson State dominated Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference champion South Carolina State 28-7 on Saturday to win its first HBCU football national championship.

Taylor is a homegrown hero, Jackson State through and through. Recruited as a quarterback, Taylor attended Jackson State on a football scholarship and played four years for the Tigers, ending his career as a wide receiver. As confetti fell on him Saturday, Taylor savored what must have felt like a surreal moment with his friends and family members who all have been part of his journey.

“To hug those people, my family that supported me, my sister who used to take me to a lot of those games … she was out there on the field with me. This means everything,” Taylor said.

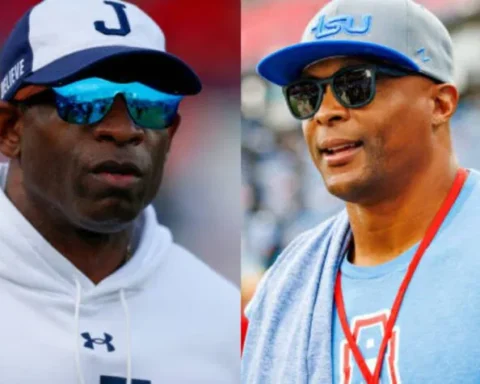

This was Jackson State’s third Celebration Bowl appearance. Taylor was an assistant on coach Deion Sanders’ staff when Jackson State made its previous Celebration Bowl appearances as the heavily favored “Coach Prime” show.

With his son, Shedeur, and the two-way star Travis Hunter, who won the Heisman Trophy on Saturday, Sanders built Jackson State into a glamour HBCU program. Each of the Tigers’ visits to the Celebration Bowl became a media circus that left opponents seething. In 2021, Jackson State lost to South Carolina State 31-10. In 2022, Jackson State lost to North Carolina Central 41-34.

After Taylor finished speaking with reporters Saturday, I asked him what was so different about this team. There were really good players, such as running back Irv Mulligan, but no superstars to speak of. Yet on Saturday they succeeded where Sanders’ two teams failed.

Why?

“It’s more of a brotherhood,” Taylor said. “Every week we find a way, whether it’s offense, or defense or special teams. They know how to stick together and play for each other.”

This game — this HBCU football national championship, this season — may have once and for all ended the Coach Prime hangover at Jackson State and in the Southwestern Athletic Conference.

In his three seasons at Jackson State, Sanders reinforced the program’s foundation. But the most important thing Sanders did was advocate for Taylor to become the next Jackson State coach after Sanders announced that he was leaving for Colorado.

Sanders would be a hard act to follow, but he knew that Taylor was born to be the Jackson State coach. Taylor bled Jackson State. After Saturday’s victory, Taylor said that since joining the coaching staff in 2019, he was preparing for his moment.

“I always prepared that way and when I had that opportunity, I pulled my sleeves up and went to work,” Taylor said. “I knew what I wanted my roster to look like, I knew what I wanted this coaching staff to look like and I knew we were going to be successful. I wanted this moment. I knew this moment was going to happen.”

Football at historically Black colleges and universities has had an abundance of moments over the years. What was often lost during the Coach Prime years at Jackson State was that these HBCU football programs have been around for a long time, and they have endured.

South Carolina State began playing football in 1907. Jackson State’s first season was 1911. They were landing places when predominantly white schools refused to recruit Black players, and where players could showcase their talents and make it to the pros.

When I was a senior at Morgan State in 1971, the first year of the MEAC, we traveled to Jackson State to play the Tigers in a non-conference game. Walter Payton, who went on the play in the NFL for 13 seasons, was a sophomore on that Jackson State team. Future Pro Football Hall of Fame linebacker Robert Brazile was a freshman linebacker and Jerome Barkum, who had a 12-year NFL career, was the Tigers’ wide receiver.

A month before our trip to Jackson, we traveled to Orangeburg, South Carolina, to play South Carolina State, which had just joined the MEAC. Future NFL star Donnie Shell may have been a freshman on that team and future Hall of Fame linebacker Harry Carson was on the way.

Every team in the SWAC and many in the MEAC had this kind of talent, though the tide was beginning to turn as white schools realized that if they were to be successful, they needed to recruit the Walter Paytons and Robert Braziles. And they did.

That so-called golden era of Black college football is long gone and will never return. The NFL will never draft players from HBCU in the numbers that it once did. The Celebration Bowl pays homage to a long-lost era while celebrating the here and now.

For young HBCU coaches such as Taylor, the mission has changed from turning out a preponderance of pro football players to providing opportunities for players to play competitive football, earn their degrees and perhaps find a pathway to pro football in the NFL or elsewhere. The HBCU universe provided an opportunity for Sanders to be stamped and validated as a football coach.

The coach’s job is mostly to provide championship moments like the moment Taylor and his Jackson State players enjoyed here Saturday. The moment Taylor could never have predicted — the moment that solidified his elevated stature at the school — took place in the fourth quarter on Jackson State’s final drive of the game.

The Jackson State fans began chanting his name.

“There were some great moments out there,” he said “I think the one that kind of blew me away was when I heard the crowd hollering my name like that. That was unbelievable. That’s a moment I’ll never forget. But to get on that stage … I’ve been waiting a long time to get on that stage and hoist that trophy up. It was an unbelievable feeling.”

There have been many great moments at Jackson State over the years. Taylor’s triumph Saturday held out the promise that there will be many more.