On the night of January 21, 1897, a mob of White men armed with pistols and shotguns surrounded the home of freed slave George Dinning in southern Kentucky. They falsely accused him of stealing livestock from a neighboring farm and unleashed a hail of bullets into his house, wounding him in the arm and forehead.

Terrified for his wife and children, Dinning fired back, killing one of his assailants.

In a remarkable story filled with dramatic twists and unusual alliances, Dinning eventually became perhaps the first Black man in the country to win damages against a White man after a wrongful manslaughter conviction.

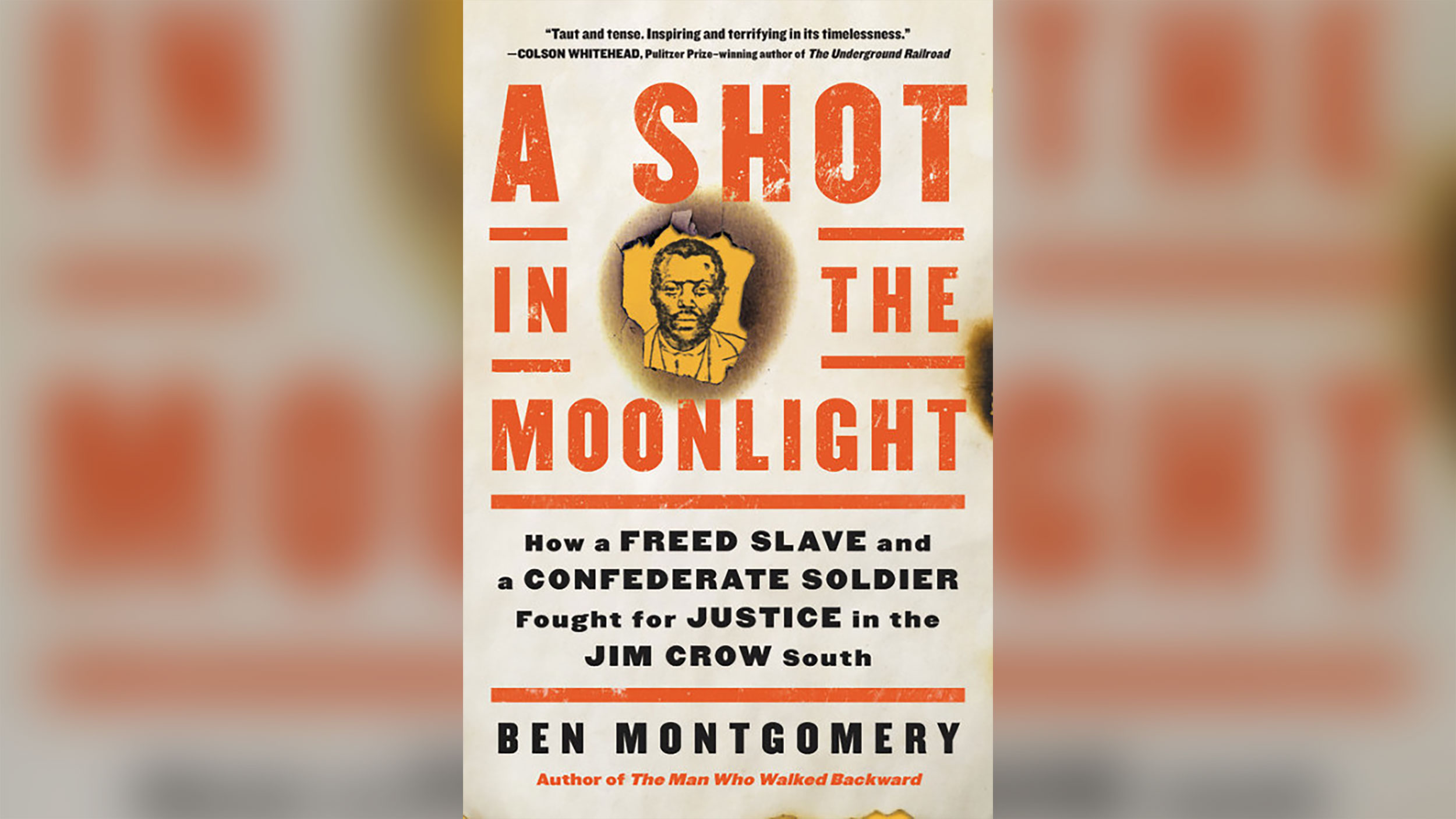

That fateful night and the harrowing months that followed are chronicled in a new book, “A Shot in the Moonlight: How a Freed Slave and a Confederate Soldier Fought for Justice in the Jim Crow South,” by Ben Montgomery.

Montgomery recounts how Dinning’s trial deeply divided the state, with lynch mobs hovering around the courthouse, waiting for opportunities to strike. Gov. William Bradley posted soldiers to protect Dinning in the jail and the courtroom.

Not surprisingly, Dinning was found guilty by a jury of 12 White men and sentenced to seven years in prison.

But then the story took a dramatic turn. In what was a bold decision for a White Southern governor at the time, Bradley pardoned Dinning two weeks after the sentencing. Bradley kept his decision a secret until the next day to give Dinning time to hop on a train out of town.

Dinning later moved to Jeffersonville, Indiana, where he changed his last name to Denning. With the help of Bennett Young, a young Confederate soldier and lawyer, he also successfully sued the men who had attacked his house that winter night in Kentucky.

For Anthony Denning, reading about his great-grandfather’s ordeal in Montgomery’s book was surreal. Denning grew up in Jeffersonville and has stashes of old newspaper clippings and historical records from years of research. But the book provided new information that filled in some gaps.

“The story has been handed down, my family talked about it a lot while I was growing up,” Denning, 59, told CNN. “But to finally read the details of what took place that night was very emotional. It gave us such a sense of pride.”

The book also shed new light on the people who helped his great-grandfather, including Young and the many Black and White people who lobbied the governor to demand justice, he said.

CNN talked to Montgomery, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, about his journey to document this largely forgotten story. His answers have been edited for length and clarity.

How did you find this story?

I spent the last three years of my stint at the Tampa Bay Times working on a massive public records project to account for six years of police shootings in Florida. We learned that in about 40% of police shootings, the victim was a Black male and that is way out of whack with Florida demographics — only about 15% of the population of Florida is Black.

I just became overwhelmed by the level of tragedy. I found myself longing for a story that involved a Black male character that didn’t end in tragedy, and I began to actively search for a story that fit that. I had to go way back to 1897 to find one, unfortunately. The more I learned about it, the more it felt pressing to tell. It was a story that happened more than 100 years ago, but … felt immediate.

The George Floyd protests led to pivotal conversations about race. Did that factor into your decision to tell this story now?

Absolutely. Not only was it a story that allowed me to talk about White violence, the history of White violence, the history of White supremacy — but it also featured a character, Bennett Young, who is the lawyer who represented George Denning in federal court pro bono. He was a complicated man. He not only founded an orphanage for Black children and represented Black men and women for free in federal court, but he also did more than any man of his era to promote the sort of Southern mythology that’s so closely akin to White supremacy. This story was a vehicle to renew our conversation about who we are and how we should remember the Confederates.

He (Young) spent a ton of his time raising money for Confederate statutes — a lot of which we’re today thinking about pulling down. He delivered the keynote address at the unveiling of the General Lee statue in New Orleans. …. so this guy was involved in a lot of things, and part of what I wrestle with in the book is how should he be remembered? Because when the war started, there’s no doubt that he came down on the side of slavery and we now judge every ancestor primarily on that fact.

I don’t think you’ll see any other contemporary man, certainly not a Southern man, who did more for Black people than Bennett Young. He was on the forefront of fighting for civil rights and at the same time leaving a legacy that would impact civil rights all the way through our time. It’s wild.

What’s the one thing that stays with you about this story?

I always think about the courage of George Denning, this man who could have been a victim, and many other people of his era who were just victimized by White people. And he simply refused to submit … and the courage it took for him to grab his shotgun and to defend his home and his family from this White mob that was attacking them. Almost brings me to tears.

It took courage to walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge for those marchers in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. It took courage for college students in Greensboro (North Carolina) to occupy that Whites-only food counter. It took courage for Rosa Parks to refuse to give up her seat on the bus in Alabama. All of those stories are spawned by these other forgotten stories from the era before, from George Denning’s era. He simply had the courage to not let himself get killed and then to go in search of retribution, and that’s such an important thing.

You met Denning’s family. What was that like?

I would not have done this story without their permission. So to meet Anthony Denning in Louisville in 2019 and to fall into his good graces was one of the highlights of my life. It’s such a treasure to connect the story from the past — this person I’d been thinking about for a couple of years. To connect him with a human in the flesh, a manifestation of his courage, was so important to me and such a beautiful moment.

Was the family involved in the book’s process?

I sent Anthony (Denning) a copy of the manuscript. I’m an interloper in this story, and I recognize that I’m a White man who has chosen to tell the story about a Black man, and I did not want to do his family wrong in any way. And so Anthony has been a part of the process. He offered feedback on the manuscript and suggested some changes. We made those changes. His family read the book, they have joined us for a couple of online, book-talk type conversations now. It’s such a treat to to not only feature this story from the past, but also to feature these people who are alive because of George Denning’s courage. They would not exist if he hadn’t done what he did.

What challenges did you face while working on the book?

I think primarily being a White guy and trying to dig into the story of a Black man. I approached this with great trepidation and sensitivity for that reason. Beyond that, George Denning was a man who, so far as I know, never learned to read or write. He died in the 1930s, so his personal record is scant. You know, there are no diaries, for instance, and there are no journals, no personal papers that can be found in an archive or a library. So the challenge for me was trying to create him as a vivid, detailed, textured human being that people could root for with such scant information. This meant spending tons of time in the archives and finding every little drip and drop of public record left behind.

Do you believe he finally got justice?

Someone asked on a book talk with his family the other day whether justice was achieved.

He won $50,000 in damages from the lynch mob in that successful lawsuit. But he never recovered very much of it, certainly not the full amount. He tried for years to get these White farmers to pay up. And they didn’t. And so that question, put to his family, was justice achieved? They said no. And hearing them without hesitation … all these men and women say, no, no, no, no, cast this in a brand new light for me.

And it’s the reason that we should be having this conversation still, because ultimately what we’re left with is a guy who won in words. He won a lawsuit, but he was stripped of the land that he had bought and paid for, his family was chased off. Imagine getting disconnected from all of your surroundings, the people that you knew and loved.

Imagine getting just scared out of that place and having to relocate 150 miles away in a place that was completely new and completely foreign to you. And then multiply that by many hundreds of thousands of people that this happened to in the South. And that is a national tragedy that we have not yet dealt with.

What do you hope people get from this story?

That we’re not finished talking about this. That Black history is not history. It is as important today to consider these stories as it was back in the 1890s. So many of the stories from that era — post-Civil War and pre-civil rights movement — have gone undiscovered. And those stories are as important to recall today as the bravery of Rosa Parks and the speeches of Martin Luther King Jr.