The death of hip-hop artist Earl “DMX” Simmons at the age of 50 represents not just an occasion for mourning, but one of celebration and commemoration for the iconic rapper who culled soaring artistry from personal trauma and grief. A Generation X impresario who burst onto the scene during the Clinton administration, DMX offered a bold reinterpretation of conventional depictions of Black culture in postindustrial urban America.

I first encountered DMX, or the X-Man as many called him, through his 1998 masterpiece, “It’s Dark and Hell is Hot.” The veritable album of the year, at least the hottest joint in hip-hop, put New York rap back on the map. As a 25-year-old New York native, writing a PhD dissertation on the Black Power movement back then, I instantly related to DMX’s lyrical flow, menacing swagger, wicked sense of humor and aching vulnerability. I recognized, like many of his millions of fans, aspects of myself in the lower frequencies of Black life that he recounted with brilliance and bravado.

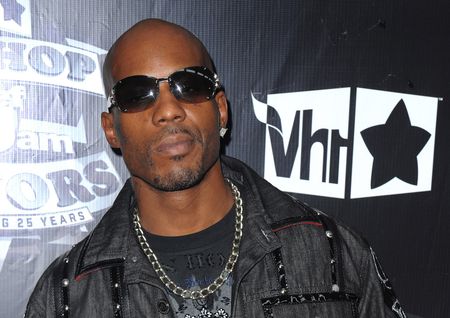

The X-Man’s public persona reflected the kaleidoscopic nature of Black masculinity in the late 1990s. DMX raged against stereotypes of Black criminality even as he invoked, then subverted, the tropes of thug, gangsta and hoodlum into a showcase for Black artistry. The image of DMX, rippling body emblazoned with tattoos, smoking a blunt on stage and galvanizing audiences all over the world represents a hinge point in the history of Generation X hip-hop lovers such as myself.

DMX’s growl, his hoarse voice and raw lyrics didn’t so much move crowds as stun them into aural submission, winning them over with the mellifluous power of the beat and the confessional nature of lyrics that interrogated Black masculinity with new depth and breadth.

If Jean Michel-Basquiat poured his pain onto the literal canvas of the masterpieces that he created (and sometimes destroyed) during his brief career, DMX turned his personal battles with alcohol and substance abuse into music that explicitly grappled with addiction, self-medication, depression, anger and grief. In doing so, he powerfully showcased Black male vulnerability in an industry that too often relied on a one dimensional view of masculinity to sell records and project subjective notions of authenticity. And his humor, dark and subversive, shone through his frank talk about sex, drugs and violence.

When the X-Man raged in “Party Up (Up In Here),” “Y’all gonna make me lose my mind up in here, up in here! Y’all gonna make me go all out up in here, up in here,” it allowed us all to root for the underdogs in ourselves. Appearing on the scene less than three years after the deaths of Tupac Shakur and the Notorious BIG, DMX and his Ruff Ryders Crew took hip-hop and American popular culture by storm and, for a time, he emerged as perhaps the most versatile rapper-actor-entertainer in the industry.

His turn as a thoughtful gangster, opposite the iconic rapper Nas, in the film “Belly” — directed by Hype Williams — remains a cult classic and offered glimpses of an immense talent that stretched from music to movies, and influenced generational fashion and style trends.

On this score, DMX paved the way for future hip-hop entrepreneurs, such as 50 Cent, who would leverage their personal biographies as street hustlers to become brand influencers and business moguls on a level unimagined during rap’s early days.

At times DMX’s well-documented troubles with the law obscured his still potent stage presence and impact on fans who flocked to him in concert and, during the pandemic, in a Verzuz battle with legendary rapper Snoop Dogg. But until the end of his life DMX fought, and at times overcame, personal demons that would have leveled the less resilient. Ultimately, the most defining aspect of DMX’s legacy will be his courageous willingness to plumb the depths of his personal trauma to produce art that will continue to shape hip-hop culture long after his death.