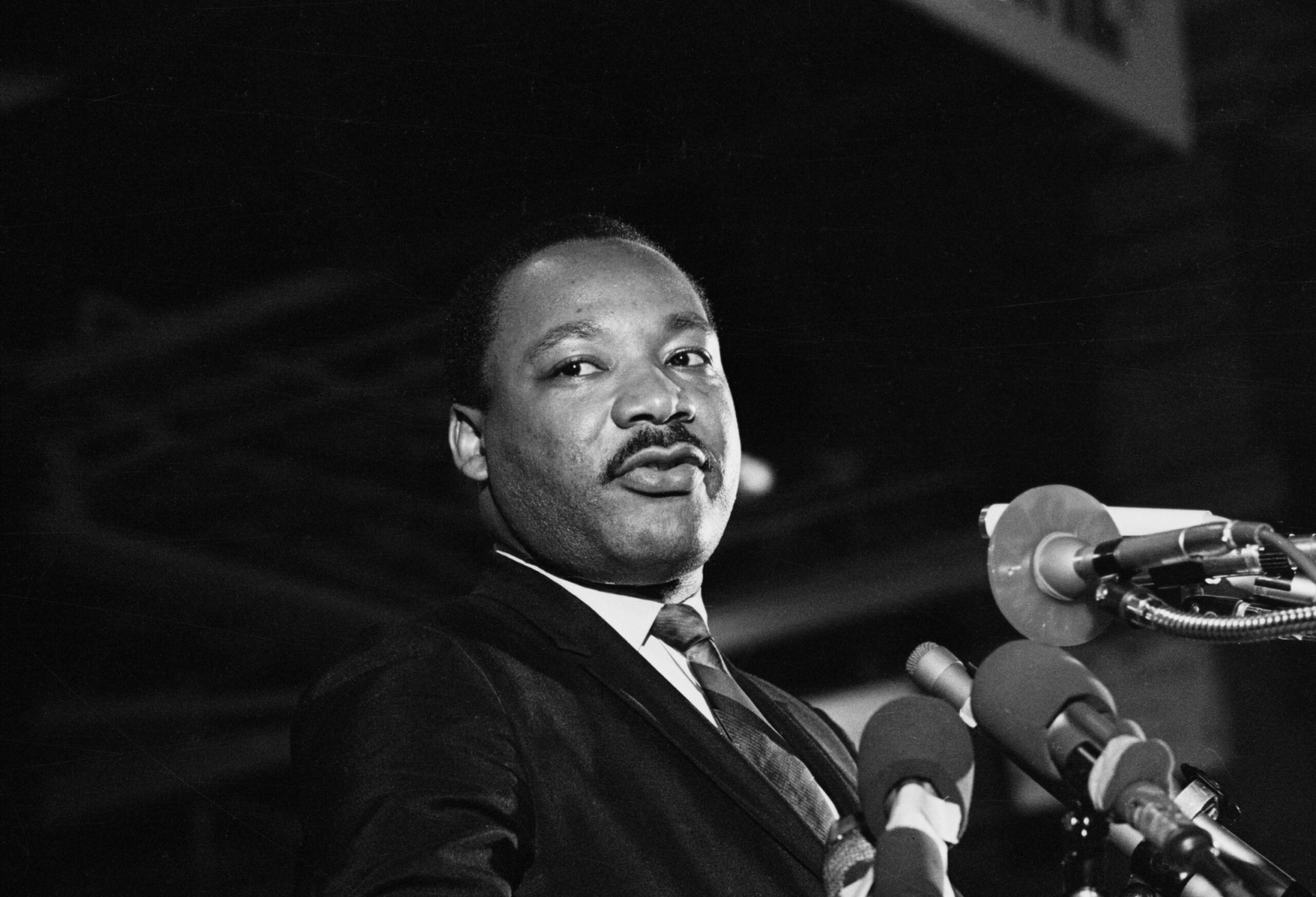

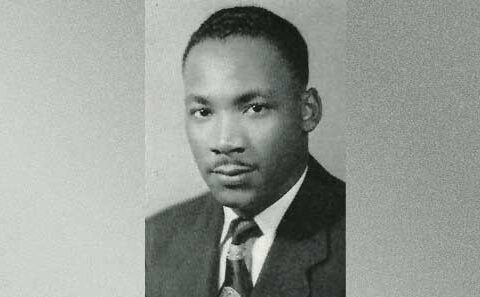

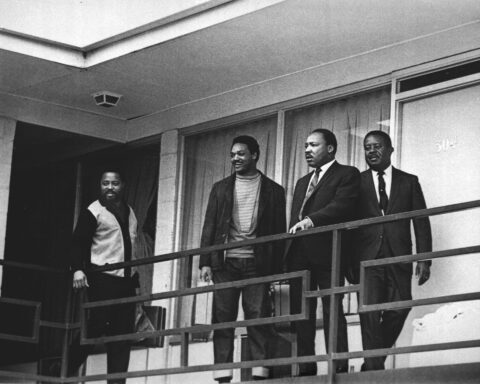

Hours before an assassin’s bullet ended his life in the spring of 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. — a father to one of us, a role model to the other — delivered his final public address to a Memphis crowd that had gathered to fight what he called the inseparable twins of economic and racial injustice.

Weaving between protest and prophecy, he famously spoke that night of reaching a mountaintop from which he could glimpse a promised land where Black people were finally free from racism and poverty. Beneath all the proverbs and anecdotes, he offered a practical roadmap to economic justice for Black America. It required uplifting community tentpoles like Black banks.

“[W]e’ve got to strengthen Black institutions,” Dr. King said. “I call upon you to take your money out of the banks downtown and deposit your money in Tri-State Bank [a Black-owned bank]—we want a bank-in movement in Memphis.”

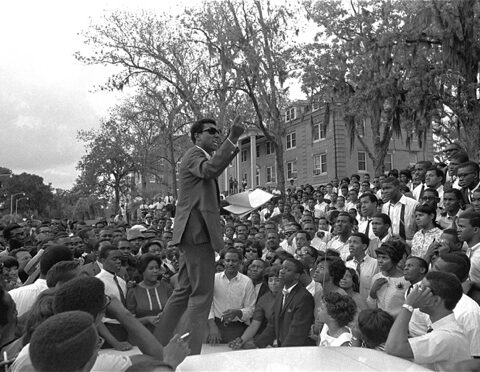

Like the sit-in protests of the 1960s that forced racial integration everywhere from lunch counters to libraries, to bank-in is to protest against the continued exclusion of Black people from mainstream financial services and against the predatory practices like check-cashing and payday loans that keep too many families trapped in redlined ghettos. To bank-in is to accelerate the long-overdue financial inclusion of Black people in America.

Despite all the gains of the Civil Rights Movement, Black entrepreneurs still struggle to keep their small businesses open and Black families fight to keep their homes at rates far higher than the national average. The economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic compounded these challenges. As a result of the pandemic, the number of Black business owners declined by over 40%, compared to just 17% for white owners, and the share of Black homeowners in forbearance is higher than the overall rate.

By supporting community-focused Black-owned banks through investments and commercial transactions, we can begin the hard work of correcting these economic imbalances principally because Black banks are the lenders most willing to lend to Black families.

Because mainstream banks have shuttered branches in poor and historical redlined communities by the thousands since the financial crisis of 2008, Black banks are often Black borrowers’ only retail source for non-predatory lending or wealth-building programs.

Recognizing the community impact of these banks, the FDIC reports quarterly to Congress on the state of minority depository institutions, or MDIs, to protect against insolvency. At the time of Dr. King’s death, there were about 50 Black-owned banks, each of them extending mortgage and small business loans to customers that mainstream banks would not. Their numbers shrunk during the savings and loan crisis of the 1980’s and again during the Great Recession, which squeezed Black households’ wealth through unprecedented foreclosures and home equity losses. Today, there are just 18.

Despite their mission to extend credit to marginalized and underbanked Americans, Black-owned banks, like all lenders, are bound by regulations limiting them to offer loans on a relative scale of their capital assets, which is a measurement of the bank’s financial strength based on interest on deposits, banking fees and the sale of stock. But unlike mainstream lenders, Black banks are chronically and acutely undercapitalized.

Dr. King was right when he said we’ve got to strengthen Black institutions. However, that requires more than just making deposits in Black banks, because deposits alone do not allow banks to create significant new lines of credit under existing banking regulations.

Capitalizing banks is more complex.

It starts with giving Black banks the opportunity to transact significant deals, as the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks did last year in a $35 million construction loan with a syndicate of 11 pooled banks, or serve as a co-lead arranger of a banking syndicate with a major bank. Deals of this sort grow the bank’s capital assets and diversify Black banks’ loan portfolio, which usually consists primarily of smaller and higher-risk deals in service of their communities.

Transacting meaningful deals with Black banks is one of those rare opportunities where good business is perfectly aligned with social welfare, because a robustly capitalized Black banking sector will chip away at America’s racial wealth and housing gaps by providing housing and small business loans to marginalized populations.

We’ll know that corporate America is sincere about racial and economic equity in this country if we see others follow the Hawks’ lead. At the National Black Bank Foundation, we’re watching and we’re willing to assist those interested in supporting the mission of Black banks.