By Bryan Mcclure

Two nights after peacefully demonstrating for the right to bowl in a segregated Orangeburg, S.C. bowling alley, Robert Lee Davis lay on the blood-filled campus infirmary grasping for life. Years later he recalled, “The sky lit up. Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! And students were hollering, yelling and running. I went into a slope near the front end of the campus, and I kneeled down. I got up to run, and I took one step that’s all I can remember. I got hit in the back.” Davis was one of the fortunate survivors that night, now remembered as the Orangeburg Massacre, which took place on February 8, 1968 on the campus of South Carolina State University. Twenty-seven other students shot that night survived. Three students including, Sam Hammond, Delano Middleton, and Henry Smith did not. These students gave their lives for the movement. Undoubtedly, the legacy of students from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) is intrinsically linked to the success of the Civil Rights Movement.

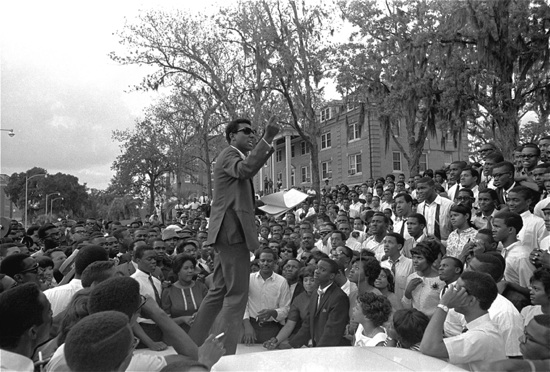

On April 15, 1960, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a crowd of over 200 students on the campus of Shaw University. Speaking at the founding conference of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), King concluded, “The youth must take the freedom struggle into every community in the South without exception.” By 1960, young Black students attending Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) operated as navigators of the rising tide of vast social and political change sweeping the nation. Although the juxtaposition of HBCUs into the Civil Rights narrative is complex, fluid, and understated, such institutions undoubtedly constituted the heart and soul of the Movement.

HBCUs served as institutions of solidarity. Dorm rooms were transformed into meeting locations; quads became rallying centers, chapel basements transformed into training grounds for non-violent protests, and campuses banded together creating an intricate system of social networks. Moreover, these institutions served as breeding grounds for the surfacing generation of Black leaders.

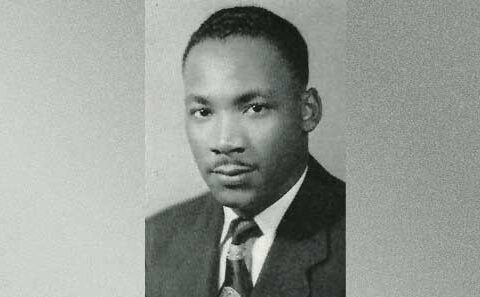

Students attending HBCUs such as King, Morehouse College, c/o 1948; Diane Nash, Fisk University, (entered fall 1959, received an honorary degree 2009); and Stokely Carmichael, Howard University, c/o 1964, emerged as key fixtures within the movement.

Preceded by his father and maternal grandfather, King’s entrance into Morehouse as a fifteen year old teenager, signaled the third generation of Kings to attend the school. Of his Morehouse experience King recalled, “As soon as I entered college, I started working with the organizations that were trying to make racial justice a reality.” High academic expectations and personal relationships also influenced King. There he was introduced to Henry David Thoreau’s essay on “Civil Disobedience.” He also forged lasting relationships with prominent leaders such as professor of philosophy and religion, George Kelsey, and Morehouse President, Benjamin Mays. King’s Morehouse experiences brought him face to face with pressing social issues of the day where he “felt a sense of responsibility,” one which he “could not escape.”

Further north in Washington, D. C. students at Howard University continued to make their voices heard. Out of the tradition of Ray Logan, Charles Hamilton Houston, and Thurgood Marshall, emerged a new group of students interested in creating new methods of combating Jim Crow. It was an environment ripe for innovation, intellectual curiosity and social antagonism. It was here where King, amongst many other students, heard President Mordecai Johnson lecture on civil disobedience and Gandhi. A few years later in 1960, a young Trinidadian named Stokely Carmichael moved into Howard University’s Drew Hall.

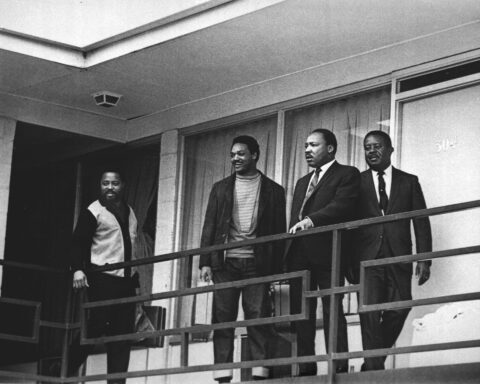

At Howard, Stokely joined a diverse student body, which included foreign students from Africa and the Caribbean. As a student, Stokely fell under the tutelage of esteemed scholars such as Toni Morrison and Sterling Brown. His days at Howard were filled with activism and intellectual exchange. Many of his peers spent countless nights at his Euclid street apartment formulating the blueprint for combating inequality. Before graduation in 1964, Stokely joined the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), the Howard branch of the SNCC, and marched with a host of leaders including the likes of Bayard Rustin.

Stokely, like many of his peers, refused to conform to the social stigmata which required them to be “nice, neat, clean, honest, and polite.” According to Stokely, students felt propelled as they “grew more confident in our organizing skills, that we students could organize effective pressure inside the nation’s capitol, in international forums, and before the world media, to ensure that the U.S. government met its obligations to black education.”

Stokely recalled, “There can be no question as to the importance of the Howard experience in my formative life, but by far the most important element of that experience—morally, politically, culturally, and even emotionally—was the movement.”

In similar fashion to Howard students, students across the nation at HBCUs were having much success organizing. Still, not all schools were able to keep pace with more progressive schools such as Howard and Shaw. State-dependent Southern HBCUs, beholden to state funds, and attempting to maintain a respectable image blacklisted would-be student activists. Felton Clarke, President of Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, for example, expelled roughly fifty student activists including H. “Rap” Brown. Undeterred, Brown persisted in his efforts, joining Stokely and others in D.C. as members of SNCC.

The cultural and political space provided by HBCUs casts students together in a way that could sustain growing momentum for the movement. In this space, they coalesced into a more organized, militant agent of social change. “I was convinced,” wrote King, “that the student movement that was taking place all over the South in 1960 was one of the most significant developments in the whole civil rights struggle.”

Out of this space emerged SNCC at Shaw University; the February First Movement at North Carolina A&T; and the Nashville Student Movement at Fisk University. King characterized the impact of these moments best: “In 1960 an electrifying movement of Negro students shattered the placid surface of campuses and communities across the South. The young students of the South, through sit-ins and other demonstrations, gave America a glowing example of disciplined, dignified non-violent action against the system of segregation.”