A year ago, George Floyd’s chilling last words, “I can’t breathe,” sent shock waves around the world. A guilty verdict came down April 20, but Black Americans had no time to celebrate the rare occurrence of a White police officer being convicted of the murder of a Black man.

The next day, Andrew Brown Jr. was fatally shot by sheriff’s deputies in North Carolina, and the officers will not face criminal charges because the district attorney ruled that the shooting was justified.

Similar scenes have played out for decades: A Black person is killed by police, protests erupt in cities across the US, the unequal treatment of Black Americans becomes the focus, and the debate over policing ensues.

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders — better known as the Kerner Commission — put out a report that attempted to address systemic racism in the US, including police violence against Black people.

The report stated that racism was a major cause of economic and social inequality for Black people and that it was moving the nation toward two societies: “One Black, one White, separate and unequal.” That, coupled with the brutal police treatment of people of color and poverty, helped spark the race riots of the 1960s.

At the time, the commission’s findings shocked many Americans because for the first time, “White racism” was noted as a major cause for the unequal status and living conditions of Black Americans, said the commission’s last surviving member, former Oklahoma Sen. Fred Harris. But the report’s findings and proposed solutions led nowhere.

More than 50 years after the report, Harris, historians and policy experts tell CNN that change will only come when the people have the will and the government is truly honest about what must be done politically, socially and economically to address racial inequality.

Jelani Cobb, historian and co-editor of “The Essential Kerner Commission Report,” tells CNN that people and institutions already know what the problem is and that the only action that needs to be taken now is actually following the recommendations of the commission, and pay the price that comes with it.

“The actions are laid out, you really don’t need more recommendations,” Cobb said. “The fundamental observations (of the commission) have never been acted on.”

Because officials never acted on the recommendations of the commission, the US has seen the same issues of policing, poverty and inequity in Black communities manifest themselves in different ways in the decades since the report’s release.

So, here’s a look back at the Kerner Commission, what it found and the solutions it suggested for, hopefully, how to move forward.

The Kerner Commission addressed policing

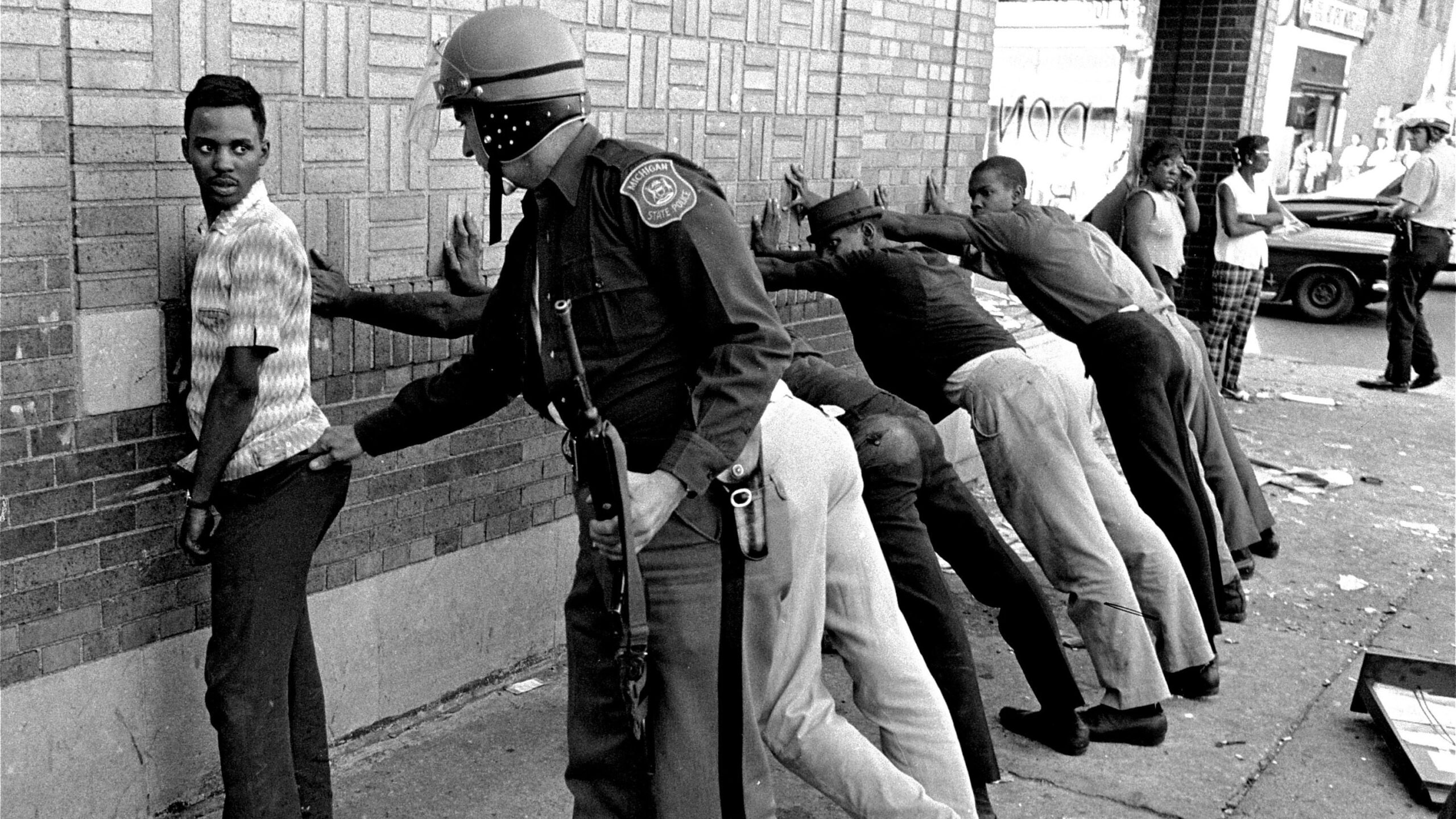

President Johnson formed the Kerner Commission in 1967 after riots erupted in Black neighborhoods in cities like Detroit and Newark.

The commission was tasked with putting out a report on the root causes of the racial unrest and offer solutions on how to prevent future riots.

The report found that many Black people viewed the police as symbols of White power, racism and repression.

“The atmosphere of hostility and cynicism is reinforced by a widespread belief among Negroes in the existence of police brutality and in a ‘double standard’ of justice and protection — one for Negroes and one for Whites,” the report read.

The report made a number of recommendations, chiefly among them the need to diversify the police force with more Black officers. It also laid out a plan for how the federal government should create, fund and support a “community service officer” program. This was a sort of pipeline for Black men between 17 and 21, the report read. The idea was, in theory, that seeing Black cops in Black communities would help establish trust in the police. The recommendation for this program also looked to improve communication with the Black community and create jobs for Black teens and young adults.

Psychologist Kenneth Clark summed up Black America’s thoughts on the commission’s report.

Clark said looking at the report was like “a kind of Alice in Wonderland” because reading it was like reading all the commissions that came before it: “The same moving picture re-shown over and over again, the same analysis, the same recommendations, and the same inaction.”

Clark was referring to the previous commissions formed to study the Chicago riots in 1919, the Harlem riots in 1935 and 1943 along with the one in 1965after the Watts Riots in Los Angeles.

Despite the very progressive ideas in tackling racism and police brutality, Johnson was infuriated by the report because he expected it to basically rubber-stamp the initiatives and social programs he already had in place, according to Steven Gillon, author of “Separate and Unequal: The Kerner Commission and the Unraveling of American Liberalism.”

“He felt betrayed by the commission and refused to accept findings,” Gillon said.

Johnson’s frustration with the report resulted in a politically conservative reaction that sent the country in the complete opposite direction of the commission’s recommendations. Decades later, that adverse reaction can be seen in the militarization of police and in the deployment of the National Guard in response to demonstrations in the summer cof 2020, which sometimes turned violent.

However, the US Crisis Project shows that the majority of last summer’s demonstrations — which brought attention and awareness to police violence against Black people — were peaceful, yet authorities intervened in 9% of them, or one in 10 protests.

The issues of racism and distrust in police, which were identified by the Kerner Commission as two of the main causes of racial unrest, are still seen today in the constant killings of Black Americans by police.

Harris, the last surviving member of the commission, told CNN seeing Floyd’s video and the protests that followed made him “sick at heart.”

“But it also, like most people, made me mad as hell,” he said.

The current issues with policing cannot be solved without addressing race.

“The underlying problem that prevents us from discussing race is racism. It’s a part of our DNA. A government report was not going to do away with that,” Gillon said.

The Kerner Commission addressed poverty and inequity

One of the main reasons for racial unrest in cities like Detroit and Newark in the 1960s were the poor living conditions of Black people, according to the report.

Harris told CNN many Black residents at the time were subjected to “terrible housing, almost criminally inferior schools, no jobs, no transportation to get out to where the jobs had moved or where the new jobs had formed.

“We said these conditions were a result of White racism,” Harris said. “We said White racism created these Black ghettos and it’s White racism which sustains them.”

The poverty rate for families headed by Black people or other races (27%) in 1969 was three times that of their White counterparts (8%), according to the US Census Bureau. In 2019, the poverty rate for Black people (18.8%) was double that of White people (9.1%), the Census Bureau states.

Sure, more Black Americans are attaining some economic prosperity, but the inequities in wealth, income and unemployment still exist.

Between the ’70s and ’90s, a number of factors contributed to there being “two Americas,” the biggest of them being White flight. As more Black families integrated neighborhoods, White families moved further out to the suburbs in cities across the US. Private schools, gated communities and racist housing policies contributed to the new economic segregation that became the new norm and whose remnants linger today.

“Life is more separate and unequal today than it was in 1968,” Gillon said, adding that White flight and deindustrialization left many Black people trapped in the urban core of many industrial cities.

The coronavirus pandemic has only deepened those inequalities. Nationwide, Black people have died at 1.4 times the rate of White people as of March 7, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, said in December institutional racism contributes to the disproportional impact the pandemic has had on the Black community. Some Black adults may be unable to social distance because they are essential workers. There is also a disproportionate prevalence of underlying health conditions in the Black community such as high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, chronic lung disease and kidney disease, Fauci noted.

“So unfortunately we have a situation where it’s sort of a double whammy,” Fauci said at the time.

These conditions are part of a zero-sum way of thinking, says author Heather McGhee who wrote “The Sum of US: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together.” McGhee says the zero-sum ideology comes from the belief that helping people of color comes at a cost to White people.

Gail Christopher, the founder of the Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation (TRHT) strategy, says Americans’ inability to see the value and worth of human beings is the reason there has not been public will to give Black people and other people of color equal opportunities.

“This is the type of society we have built, where we fear each other and that’s not healthy. I have a background in health, and racism is killing us,” Christopher said. “We’re not supposed to live in a state of fear and anxiety.”

Kerner Commission addressed solutions

The last question that needed answering in the Kerner Commission was: What can be done to prevent race riots from happening again and again?

Harris told CNN he and the other members of the commission decided there were no short-range solutions.

“We recommended (a) great, new federal program, vigorous enforcement of the recently enacted Civil Rights laws. But also great new programs in regards to jobs, housing and health and education,” Harris said.

Unfortunately, the commission came at what historians call “a political moment.”

Johnson was facing heat from the left with the controversy over the Vietnam War and his response to civil rights. Despite the passage of landmark legislation like the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, many activists wanted more in terms of tackling systemic issues, according to Julian Zelizer, professor of history at Princeton University and a CNN contributor.

On the right, conservatives were putting pressure on Johnson to cut the “Great Society” programs to fund the Vietnam War, Zelizer said.

“There was so much pressure on Johnson from both sides, and at a time when the United States was becoming more divisive on core issues,” Zelizer said.

Johnson decided not to run for a second term, and the commission didn’t produce any tangible results.

In the more than 50 years since then, politicians have formed a number of commissions looking at race and policing, including President Barack Obama’s 2015 Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio launched a racial justice commission in March that will be tasked with dismantling structural racism and addressing the disparities laid bare by the Covid-19 pandemic.

A new bill in the House and Senate is looking to create another commission. In February, Rep. Barbara Lee of California and Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey reintroduced legislation to establish a US Commission on Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation. Lee first proposed the bill last June, but it died after not receiving a vote.

Lee told CNN she hopes the commission can determine what policies will help close the wealth gap, address the disproportionate number of Black Americans who face unemployment and mass incarceration, improve health care access and combat vaccine hesitancy in the Black community.

The bill reflects a strategy created by Gail Christopher in 2017 that looks to eliminate racism starting at the grassroots level and working its way up to lawmakers. Since its creation, the strategy has been implemented in cities like Dallas, which created an Office of Racial Equity in its school division. At least 29 college campuses across the US have TRHT centers, Christopher told CNN.

“It’s the answer to Kerner,” Christopher said. “This is about capitalizing the public will to solve the problem in communities across America.”

Unlike the Kerner Commission, which was “a bunch of thought leaders” coming together to study a problem, Christopher said the TRHT commission is “galvanizing community action across the country.”

Gillon, the historian, told CNN the only way there is going to be significant change in the Black community is the federal government playing a role. However, people in 2021 have less faith in government so it will be difficult for the government to be involved if the people do not trust its institutions.

Zelizer, the Princeton history professor, said creating meaningful change is twofold. Activists have to create political pressure at the grassroots level in order to get the general public thinking about what is and is not tolerable in society. The other very important component is the governmental institutions seeing the need for change.

“You need to change the laws, you need to change the institutions, you need to reform things, otherwise the problems just perpetuate themselves,” Zelizer said. “So I think that has to be the end goal.”