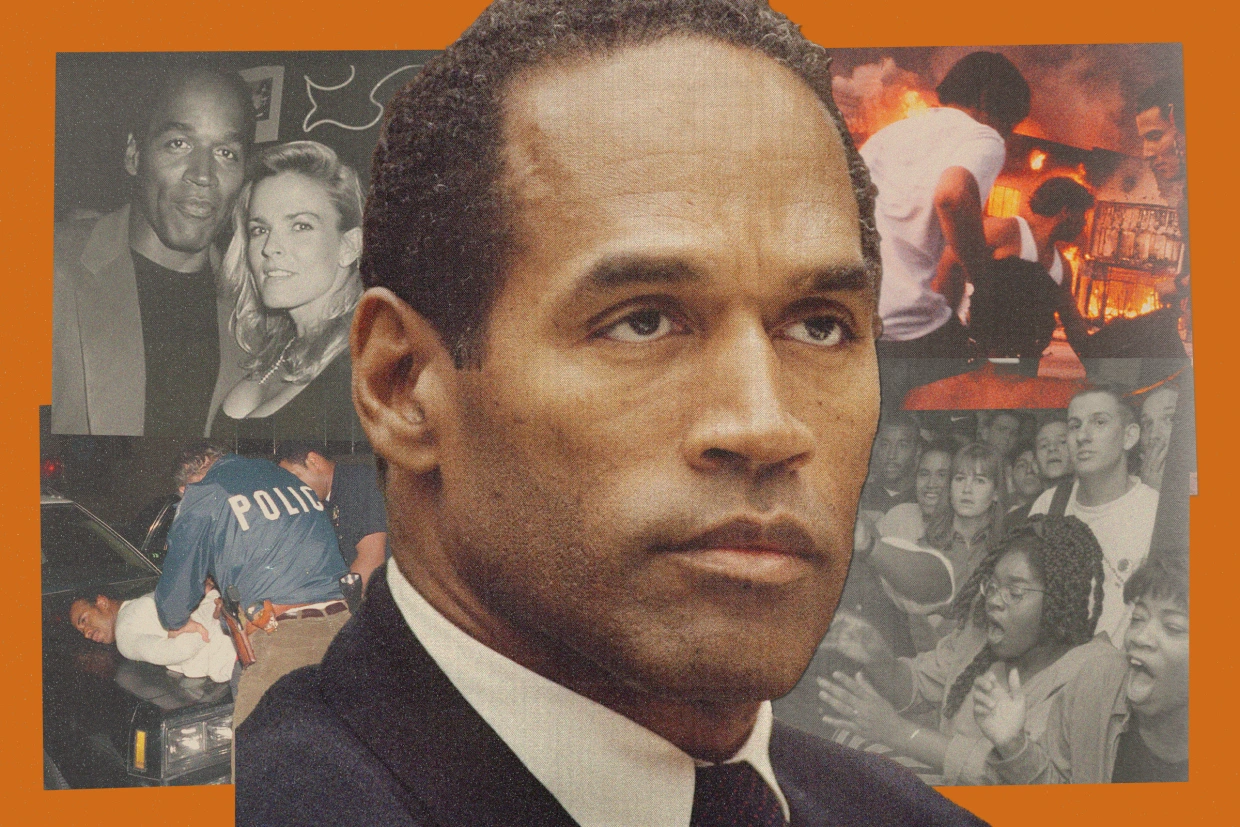

On Oct. 3, 1995, Black residents in parts of Los Angeles spilled out onto the street, cheering and passing celebratory drinks. The world had just learned that O.J. Simpson had been acquitted of double murder.

“Everybody was running out of their house, screaming and happy,” recalled journalist and cultural critic Jasmyne Cannick, who was a teenager living near Compton when the verdict came down. “I remember that. People had been glued to their television sets” for months on end, wondering where the jury would land.

The celebratory scene in Cannick’s neighborhood that day was duplicated in Black communities across the country, as the nearly yearlong so-called Trial of the Century came to an end. Simpson, then a movie star and a beloved former football player, was acquitted of murder charges in the death of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman.

The reaction to the verdict was far different among white Americans, revealing the trench-like racial divisions that were roiling the nation at the time. In 1994, 22% of Black respondents to a Washington Post-ABC News poll said they thought Simpson was guilty of the charges, versus 63% of white people. As time went on, particularly after Simpson was found liable in 1997 in a civil case brought by the Brown and Goldman families, 57% of Black people in 2015 said they thought he was guilty. Eighty-three percent of white people agreed.

“White people were like ‘guilty guilty guilty’ — there were families that broke up, and family members who would not speak to each other over the O.J. Simpson case,” Cannick said. “It was as vicious as the Trump situation. People just felt so strongly one way or the other.”

With the trial’s every detail broadcast in wall-to-wall coverage on cable news — a pure anomaly at the time — Simpson’s downfall symbolized something deeper to many Black people, particularly with the 1992 L.A. riots still fresh in their minds.

“The African American community has accepted him not as an athlete or a hero, but as someone in the criminal justice system who, like them, would have been railroaded, they would say, if he had not had a Johnnie Cochran there to rescue him,” said Charles Ogletree Jr., a Harvard Law School professor who told PBS’s “Frontline” in 2005 that as Simpson became more successful, he seemed to become increasingly disjointed from Blackness. (Cochran was a key member of Simpson’s legal defense team.).

“O.J. Simpson was raceless,” said Ogletree who founded Harvard’s Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice and died last year. “He was not a person who spent time in African American communities. He was not a person who was deeply committed to African American values.”

Simpson, who died Wednesday at 76 from cancer, came from humble beginnings, raised in housing projects in San Francisco. He played football for the City College of San Francisco before transferring to the University of Southern California, where he was part of the 1967 national championship team. The next year he won the Heisman Trophy and was the No. 1 overall pick for the Buffalo Bills in 1969. He played in the NFL for 11 seasons and, over those years, his charm and good looks threw him further into the spotlight.

His rise on the field came as American culture was shifting, following the intense peak of the civil rights era.

“He wasn’t just a household name to sports fans, but he became a household name to all of America,” said Shemar Woods, a professor at Arizona State University, who teaches sports journalism. “He was a real celebrity. We talk about influencers in this day and age, but you might say he was one of the original influencers.”

Soon enough, he became the face of major brands like Hertz, Chevrolet and TreeSweet Orange Juice in a steady stream of commercials, ensuring his wealth and fame. Eventually, that charm led him to television and movies.

“Add in the fact that he was Black, in the late 1960s — seeing a Black face in these prominent positions,” Woods said. “Certainly the Black community looked up to him and revered him as a figure that people wanted to watch. You just didn’t see that many Black people in these positions.”

To many Black people, Simpson embodied the American dream. Conversely, however, it was becoming clear that O.J. was not exactly keeping his roots in mind during his ascent.

It emerged that he would tell close friends, “I’m not Black, I’m O.J.” — an apparent recognition that he understood how his fame seemed to transcend his race in the eyes of white fans.

“Especially as a Black athlete at that time, it’s hard not to get caught up in this lifestyle and forget where he came from and forget his roots, and forget about the people who truly cared for him as a person, and not about his ability to carry a football or act in a movie,” Woods said. “Different people viewed him differently.”

By the time Simpson was pursued by LAPD in a slow-speed chase on a Southern California freeway in 1994, Los Angeles was already on a low boil of deep-seated racial tensions and Black animosity toward police.

Cecil Rhambo, now the chief of police for Los Angeles International Airport, was a sergeant with the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department at the time and had begun overseeing its internal affairs office between the Rodney King beating and the Simpson trial.

“On the heels of Rodney King, there was always some hostility” from the community, Rhambo said.

In 1991, four white police officers were captured on camera beating King. The next year, Los Angeles erupted in violence after the officers were acquitted of nearly all charges, including assault with a deadly weapon and use of excessive force, and deadlocked on one assault charge.

Rhambo said that after the King verdict, some Black Angelenos would chide him and fellow sheriffs, saying they were only there to cover things up, while others would quietly thank them for their work. He said that distrust and unrest paved the way for “differences in the way we police,” including higher expectations of accountability and the use of tools like body cameras.

Cannick, who as an advocate has taken Los Angeles’ police force to task in several high-profile cases of alleged police brutality and misconduct, says that she has seen an observable difference in the way the media covers crime in 2024, versus 1995, or even 1992. The contrasting outcomes for the trials of King and Simpson were both factors in that change.

Rhambo, who is Black and Korean, said that he remembers that while on duty during that era, he often had to remind the sheriffs who worked for him to remain neutral.

“Everybody was asking us if we thought he did it,” he recalled.

Off duty, in casual settings around other Black people, Rhambo said most people believed it was more likely than not that Simpson was guilty.

For many Black people, even if the evidence pointed to guilt, there was more on trial than the crimes themselves. The revelation that Detective Mark Furhman had used the N-word prolifically, and other injustices by local police, which were highlighted by star attorney Cochran, combined with the dust still settling from the L.A. riots, meant the case was open-and-shut to them: Simpson was not guilty.

“He symbolized the Black man and the criminal justice system at the time,” Cannick said. “Him beating the case, at the time, was everybody beating the case. We finally won one.”