Robert Parris Moses, who passed away this week at the age of 86, is the most important civil rights activist most Americans have never heard of. He died on what would have been the 80th birthday of Emmett Till, the Black boy lynched in 1955 whose open-casket funeral put the violence that defined Jim Crow Mississippi on national display.

Throughout his life, Moses shunned the limelight but, for a time during the first half of the 1960s, it came anyway. As the architect of Freedom Summer in 1964, Moses came to embody one of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee’s (SNCC) most hopeful, enduring slogans: “Come, let us build a new world together.” Though historically Moses has not received the credit he deserved because he did not consciously seek the spotlight, the legacy of this giant was and is everywhere.

Moses represents the best of a generation of radical democratic activists whose efforts helped to change American society in ways that are still contested and unfolding. His story, one that is full of twists and turns, reflects the ongoing struggle to achieve multiracial democracy in a nation founded in racial slavery.

President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris each offered statements of tribute to Moses’ heroic activism. And with good reason. Bob Moses came early to social justice activism early and stayed late.

The unlikely icon changed Mississippi

A Harlem-bred graduate of the prestigious Stuyvesant High School, Moses graduated from Hamilton College, and pursued a Ph.D. in philosophy at Harvard University before abandoning his studies after his mother’s untimely death to care for his emotionally devastated father. In 1960, when the sit-in movement began, Moses left his job teaching math at Horace Mann High School in New York City to join the movement. His initial ambition to work for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. turned, by accidental good fortune, into a fast friendship with Ella Baker, the veteran organizer who founded SNCC.

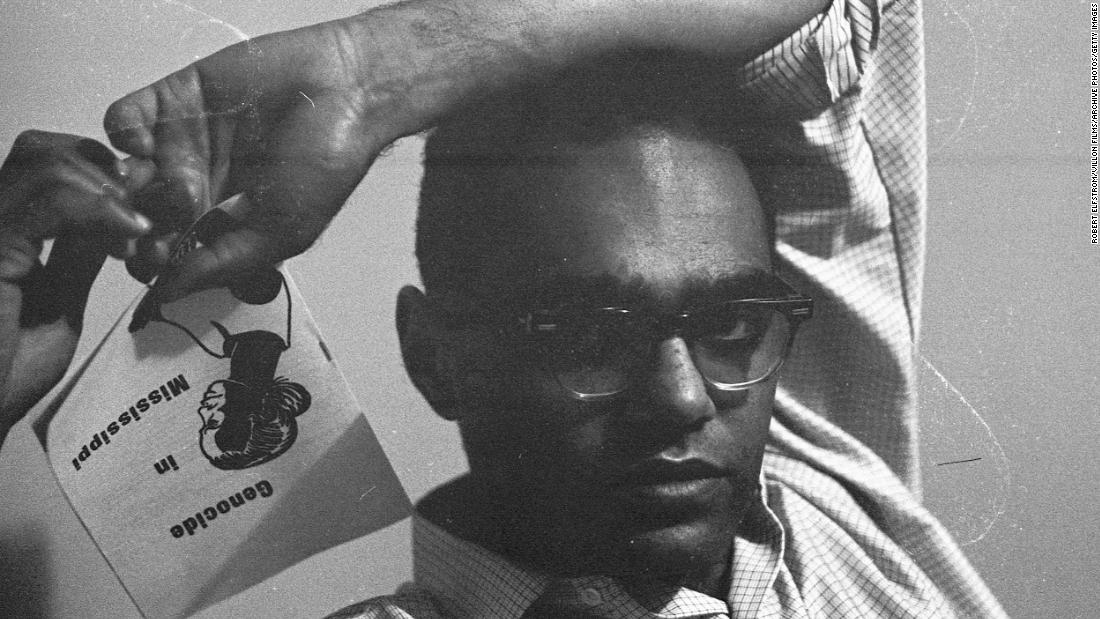

Moses would become SNCC’s key organizer in Mississippi. With his horn-rimmed glasses, baby face and denim bib overalls, Moses became an unlikely icon; the further he strayed from the trappings of celebrity, ego and fame, the more of a following he attracted. The mathematician in Moses regarded democracy as a test that required political experimentation, strategic flexibility and the ability to leverage grassroots ambitions in service of national change. The philosopher in him proved capable of inspiring colleagues, who ranged from future Black Power leader Stokely Carmichael to student activist (later documentary filmmaker) Judy Richardson.

In the towns of Mississippi, Bob Moses directed the first of SNCC’s many voting rights projects and galvanized much of the momentum that defined civil rights advocacy throughout the 1960s. Moses’ 1961 sojourn in McComb in Pike County in particular set off political shockwaves that transformed America. Confronting segregation, Black poverty and Jim Crow, Moses observed White supremacy in the raw. Black residents courageous enough to support his voting rights efforts suffered violence and he himself was arrested and assaulted. In a letter from jail, Moses described Mississippi as the “middle of the iceberg” of racial hatred that he devoted his entire life to confronting.

Freedom Summer, three years later, represented Moses’ most audacious effort of the civil rights era. He proposed, over objections from supporters and critics alike, a two-month proving ground for American democracy in the Magnolia State. Recruiting over one thousand predominantly White volunteers destined to interact with an overwhelmingly poor, Black, and rural communities where voting had ceased to exist after Reconstruction. Moses held the ability to inspire local Black folk, White volunteers and Black students eager to be of service to a cause they all instantly recognized as larger than themselves. Both sets of Black and White volunteers and Black residents faced threats from Mississippi law enforcement and White vigilantes, who in many cases were difficult to distinguish from one another.

The murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Mickey Schwerner (two White volunteers and one Black) in Mississippi made national news that summer; their bodies were recovered in an earthen dam in August, and before that the search for them in local rivers recovered body parts of dead Black people. Despite this and other brutal acts of violence, Freedom Summer went forward, with volunteers organizing Freedom Schools, civics classes, libraries, mass meetings and cultural and arts events in parts of the state where Black people had long been denied any access to citizenship at all. Also in 1964, after Black people were excluded from the all-White Mississippi delegation to the Democratic National Convention, Moses helped create the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and was part of an effort with the candidate for vice president, Hubert Humphrey, to have their delegation recognized.

Freedom Summer’s enduring influence

Freedom Summer’s influence — and Moses’ — persisted throughout the 1960s and beyond. White participants, such as Mario Savio, organized social justice movements like the Berkeley Free Speech Movement on college campuses that amplified work already being done by Black activists. Moses’ efforts catalyzed anti-war and anti-imperialism activism within and outside of SNCC and the Black Freedom Movement. Moses decried America’s indiscriminate use of force domestically and overseas in the name of freedom and democracy. He linked anti-Black violence, poverty, and segregation at home with America’s imperial dreams abroad. Years before Martin Luther King Jr. took a decisive stance against the Vietnam War, Moses plaintively asked a journalist, “What do you do when the whole country has a sickness?”

He answered his own question through action. He viewed the brutality of White supremacy in the South not as a regional aberration but as a mirror reflecting the national soul of America.

Bob Moses did not escape the tumult of the 1960s unscathed. Moses battled through depression and feelings of defeat but renewed his political faith in radical social change at every step of the way. For a time, he changed his name to Bob Parris (his middle name) and in 1965 at a SNCC conference in Atlanta held at Gammon Theological Seminary announced to stunned colleagues, “I will no longer speak to White people.” In 1966, he left America for Tanzania where he spent a decade teaching math.

Upon returning to the US, he founded The Algebra Project, devised to offer a high-quality math education to predominantly Black public-school children who faced innumerable challenges even after the civil rights victories Moses helped to orchestrate. He likened the absence of math education to the voter registrations movements of the 1960s.

The recipient of a MacArthur “Genius grant,” Moses also generously spent time recounting his movement days to younger generations of scholars and writers (including this one) eager to capture the spirit of the times from a figure whose analytical, soaring mind remained grounded in the struggles of the Black quotidian. I spoke with him by telephone in the process of researching a biography of Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture) and found him to be patient, insightful and perceptive. He answered questions he undoubtedly heard before as if they were revelatory and fresh.

Moses should be remembered as a patriot who endeavored to do the back-breaking labor of registering Black people to vote in places where they lived under a feudal system of racial oppression: small towns run by White families whose legacies could be traced back to antebellum America, where anti-Black violence was normalized as ordinary, mundane even. He confronted, struggled against and came to understand that changing these circumstances required more than legal and legislative reform, although these were important ingredients. Hearts and minds needed healing — but he knew even that was not enough.

We haven’t yet reached “enough.” Moses, as a SNCC leader, anti-war activist, math educator, husband, father and citizen set the United States on a better course; we owe him an immeasurable debt of gratitude that can only be repaid by taking action in our own lives to continue his work.