At first, Clint Smith had trouble making out the objects beside a white picket fence in the distance. Then he drew closer; what he saw made him shudder.

Planted in a garden bed in front of the fence were the heads of 55 Black men impaled on metal rods, their eyes shut and jaws clenched in anguish.

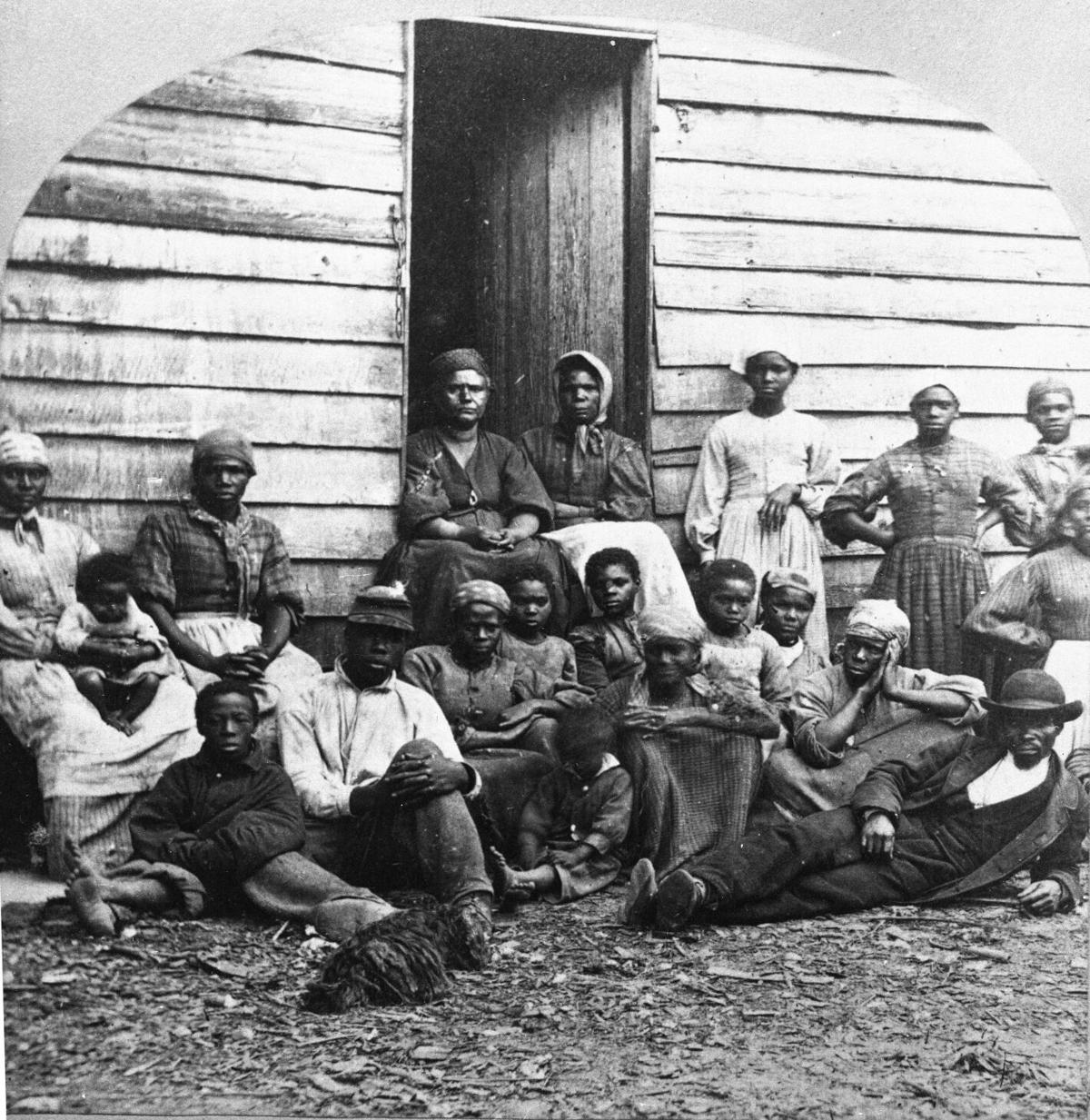

Smith, a journalist and a poet, was visiting the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana as part of his quest to understand the impact of slavery in America. He had spent four years touring monuments and landmarks commemorating slavery across America and in Africa, but his stop at the Whitney, in his home state, stood out.

There he encountered no mint juleps or “Gone with the Wind” nostalgia about slavery. Instead, the plantation displayed statuettes of impoverished, emaciated Black children. Oral histories included an account from an enslaved woman who recalled how her master would come at night to rape her sister and “den have de nerve to come round de next day and ask her how she feel.”

The plantation’s harrowing centerpiece, though, was what made Smith stop in his tracks. The severed heads were ceramic sculptures — a memorial to the largest slave rebellion in US history. In 1811 some 500 slaves, led by a mixed-race slave driver named Charles Deslondes, marched through Louisiana in military formation before federal troops captured them. Their leaders were tortured and beheaded, with their heads posted on stakes as a warning to other slaves.

The scene is one of many searing moments Smith captures in his New York Times bestseller, “How the Word is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America.”

There is no other book on slavery quite like it. Smith explores slavery’s impact on the present as much as on the past. He takes readers to places such as modern-day New York City on Wall Street, where the country’s second-largest slave market once stood on Wall Street, to show how the story of slavery is still being debated, distorted and denied.

Smith also visits such landmarks as Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello plantation in Virginia and Goree Island in Senegal, a notorious slave-trading center. Along the way he speaks with tour guides, descendants of slaves, tourists and even members of a neo-Confederate group who tell him that slavery wasn’t the main cause of the Civil War. Others tell him there was no such a thing as a “good” slave master.

Smith’s book is a systematic takedown of many myths about slavery, including one that the Whitney exhibit disproves — that most slaves just passively accepted their fate.

“From the moment Black folks arrives on these shores, they were fighting for liberation,” Smith says. “They fought for freedom that they never had the opportunity to see, but they fought for it anyway because they knew that someday someone would. When I see that at the Whitney, I think of all those sacrifices.”

CNN talked to Smith recently about his book and how slavery still informs today’s America. The conversation was edited for brevity and clarity.

How do you respond to people who say, ‘Why should I care about slavery? It happened centuries ago. I didn’t own any slaves, and neither did my ancestors. Why are you trying to make me feel guilty for something I didn’t do?’

Part of what is important is understanding how this story we tell ourselves wasn’t that long ago at all. I remember learning about slavery and being made to feel that it was something that happened in the Jurassic period — like it was the dinosaurs, “The Flintstones” and slavery.

I always think now about the woman who opened the National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016 alongside the Obama family, who rang the bell. She was the daughter of an enslaved person — not the granddaughter or the great-granddaughter. She was the daughter of someone born into intergenerational, chattel slavery.

My grandfather’s grandfather was enslaved. So when my grandfather was sitting on his grandfather’s lap I’m reminded that in the scope of human history, this was just yesterday.

The idea that an institution that existed for 250 years and has only not existed for a little over 150 years. An institution in which there are people who are alive today who were loved, raised by, and in community with people born into chattel slavery. The idea that that would have nothing to do with what the contemporary landscape of inequality looks like today is morally and intellectually disingenuous.

When people talk about what makes America exceptional, what made us so economically powerful, they often talk about American ingenuity, can-do spirit, and people like John D. Rockefeller. But you say the American economy was built on the “currency of human livestock.” How was slavery crucial to the way this country’s economy grew?

One of the most telling examples of the relationship between slavery and the economy is that in 1860, four million Black people were enslaved. Black people were worth more than every bank, factory, and railroad combined. The four million Black people were worth more than all the manufacturing in this country before the Civil War began.

Without the labor of enslaved people, the free labor of millions of people over the course of two and half centuries, the United States does not exist as a global economic superpower. It’s that simple. We cannot disentangle our rise to global economic superiority from the fact that millions of people worked for free for more than two centuries.

That had an impact not only on the Southern economy but the Northern economy. Capital and resources were what allowed the slaveocracy of the South to continue to flourish. There was an investment across the country in the perpetuation of slavery. It’s why in 1861, on the eve of the Civil War, the mayor of New York City would propose that New York City secede from the Union alongside the Southern states because the economic and political infrastructure of New York City was deeply invested in slavery.

If we did come to terms with the impact of slavery, how do you think this country would be different?

We would recognize that the reasons why America’s economic, social and political dynamics exist in the way they do are not by accident. It is very much a result of this history, whose legacy still shapes everything we see today. It would give a sense of why racial inequality looks the way it does today.

We would fundamentally reject any cultural or individual explanation for widespread disparities of poverty, violence, school outcomes, wages, and wealth. And instead, we would say, ‘Oh, it’s very clear that this is the natural result of what was done to a group of people over generations in ways which we have not made amends for.’

Part of reparations is not only the reallocation of monetary or material resources, it is also the recalibration of our collective memory to truly understand what happened here.

Do you support reparations for African Americans?

Absolutely.

What would you tell people who say if we do offer reparations to descendants of slaves, Native Americans can say, ‘What about us?’ Where does this stop?

I would say that Native Americans should get reparations. The sort of slippery slope argument is not convincing to me. I believe that Black people should have reparations for the historical wrongdoings that Black people have been subjected to. I believe that indigenous communities should have reparations for what they’ve been subjected to. Those things aren’t mutually exclusive.

I don’t think this idea that if you give it to one group of people, you’re going to end up giving to a whole bunch of people is convincing or epically inconsistent. America has a lot of accounting to do for what it has done to different groups of people.

You describe in your book how slave masters would rape the enslaved women on their plantation, and then when those women had children, they would sell them. They were, in effect, selling their own children off into slavery. What was the psychological impact on men who did that?

We see this most famously through Thomas Jefferson. People had ways of justifying it to themselves. People find ways of doing evil things and convincing themselves that they aren’t evil and aren’t as bad as other people. It becomes this exercise in moral relativity where Jefferson can write in one document that all men are created equal and write in another that Black people are likely inferior to Whites in both body and mind — where he can write one of the most important documents in the history of the Western world and also enslave over 600 people, his own children.

And that he can carry on a relationship, to the extent it can be called a relationship, with Sally Hemings for over 40 years and believe it to be consensual when it is impossible for there to be any semblance of consent when she is his human property. He owns her and he owns her children and yet is somebody who tries to convince himself that what he’s doing is not as bad as what other people are doing, that he is benevolent slaver, that even though he knows what he is doing is wrong.

Slaves did more than just survive. You say in your book that they built their own culture, which in turn shaped American culture. How did they do that?

Anti-Black racism manifested through slavery is one of the worst things this country has ever done, alongside Native American genocide. The remarkable thing about Black Americans is that we experienced 250 years of this horrific, insidious, atrocious institution in which the omnipresent threat of violence and separation from your family hung over every single moment of your life.

In spite of that, Black people created the music, the food, the culture that has shaped not only American society but global society. Out of this racism, out of this experience of being inundated with White supremacist violence, Black people were able to create something that would go on to define and create music and art and language and literature that would shape how America exists and understand itself.

The blues and jazz and hip-hop, and the visual arts of the Harlem Renaissance, and literature from people like Frederick Douglass and Zora Neale Hurston to Alice Walker, those are shaped by a legacy of trauma. Black people have taken that trauma and regularly turned it into art.

Are you okay with people using the word “plantation,” or would you prefer another term?

Plantation is fine, as long as we’re clear what they were. They were intergenerational sites of torture and exploitation.

Your book depicts your meetings with people who deny this history. How do you not lose hope for the future of this country when you’ve met so many White people who are in denial about slavery’s impact?

My orientation for this book was one of curiosity. I just wanted to understand how people understood and made sense of and situated themselves in American history. A genuine curiosity was the governing force behind this book.

There were certainly moments when I did feel angry. I don’t operate under any pretense of objectivity. I’m deeply invested in the subject matter of this book, which is why I spent four years writing it.

When I’m at the Blandford Cemetery and spending time with the Sons of Confederate Veterans, it’s not that I’m not having an emotional response to what they’re saying. But if I allow that visceral response to manifest itself in the form of anger, then it’s going to become an antagonistic interaction rather than one that is more open.

I knew that if I wanted people to tell their truth, I had to listen, and I had to be open to things I disagree with and things I profoundly disagree with.

In terms of hope, so many activists and writers that came before me say that hope is a discipline. Hope isn’t passive. Hope demands active and proactive work. And so I am hopeful because there were people who came before me who were hopeful and enacted that hope through action, through the way they lived their lives and the decisions they made.