By Emma Tucker

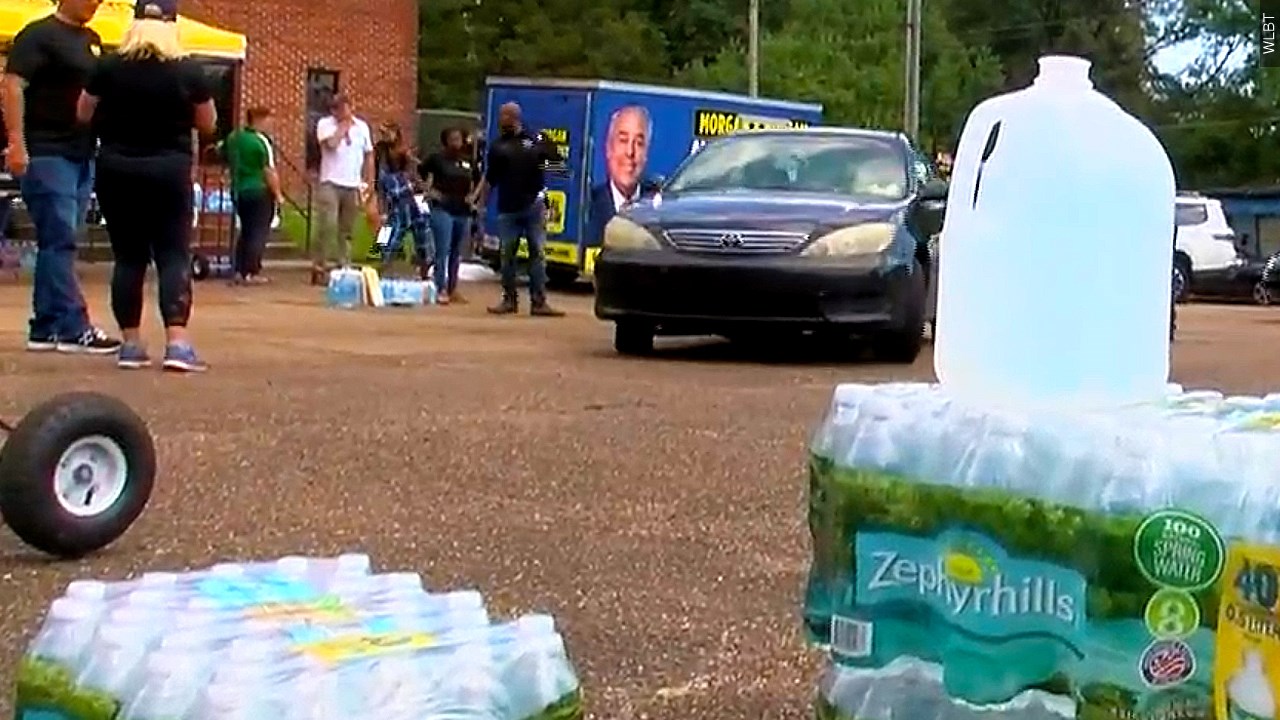

Jackson had been without reliable tap water service since Monday, when torrential rains and severe flooding helped push an already-hobbled water treatment plant to begin failing. Roughly 150,000 residents are being forced to buy water or rely on an inefficient system of bottled water pick-up sites for water to drink, cook and brush teeth as businesses and schools were shuttered.

“It’s like we’re living in a nightmare right now,” said Erin Washington, 19, a sophomore. “We can’t use the showers, the toilets don’t flush,” she said.

Washington said the campus already had low water pressure and the toilets wouldn’t flush Sunday, and by the next day, students had no access to running water. Tuesday, the water turned on for a “split-second,” but it was brown and muddy, she added.

Wednesday, the water supply turned off completely, which Washington said was the “last straw” for her. She booked a flight back home to Chicago in the afternoon and is waiting to hear from university officials on whether they will go back to in-person classes next week.

The university’s head football coach, Deion Sanders, also said its football program is in “crisis mode.”

University officials scrambled to make provisions for the 2,000 students who live on campus as they continue to experience low water pressure, university president Thomas K. Hudson told CNN on Friday.

The university switched to virtual learning Monday, a familiar shift for many students whose in-person classes were canceled and moved online in 2020 to mitigate the spread of Covid-19. School officials are monitoring the water pressure “in hopes of resuming in-person classes next week,” Hudson said.

Rented portable showers and toilets have been set up across the campus and water is being delivered to students, Hudson said.

Hudson told CNN earlier this week Jackson State has a stash of drinking water it keeps for emergencies. The university is also bringing in clean water to keep the chillers operating for air conditioning in the dorms, he added.

“It’s their frustration that I’m concerned about,” Hudson said. “It’s the fact that this is interrupting their learning. So what we try to do is really focus on how we can best meet their needs.”

Jackson water system has troubled history

The water system in Jackson has been troubled for years and the city was already under a boil-water notice since late July. Advocates have pointed to systemic and environmental racism among the causes of Jackson’s ongoing water issues and lack of resources to address them. About 82.5% of Jackson’s population identifies as Black or African American, according to census data.

The main pumps at Jackson’s main O.B. Curtis Water Treatment Plant around late July were severely damaged, forcing the facility to operate on smaller backup pumps, Gov. Tate Reeves said this week, without elaborating on the damage, which city officials also have not detailed.

The city announced August 9 the troubled pumps were being pulled offline. Then, last week, heavy rains pushed the Pearl River to overflow, cresting Monday and flooding some Jackson streets, while also impacting intake water at a reservoir which feeds the drinking water treatment plant.

Jim Craig, senior deputy and director of health protection at the Mississippi Department of Health, said a chemical imbalance was created on the conventional treatment side of the plant, which affected particulate removal, causing a side of the plant to be temporarily shut down and resulting in a loss of water distribution pressure.

A temporary rented pump was installed Wednesday at the plant, and “significant” gains were made by Thursday, the city said, with workers making a “series of repairs and equipment adjustments.”

It’s still unclear, however, when potable water will flow again to the city’s residents. On Thursday, people of Jackson were advised to shower with their mouths closed.

Hudson said the university is receiving “an overwhelming amount of support from organizations and individuals who are contributing potable water, bottled water and monetary donations through our Gap Fund,” which provides financial support to students for emergency expenses.

“We will continue to work with the City of Jackson for updates on their progress to resume operation at the water treatment facility. In the meantime, the university will remain open to house our resident students during this holiday weekend as needed,” he said, referencing the Labor Day weekend.

City officials reported Saturday most of the city’s water pressure is being restored, but a boil-water advisory remains in place, and pressure is expected to continue to fluctuate as repairs continue. The city said workers are fixing automated systems to support better water quality and production.

‘I thought this would be my first normal year’

Trenity Usher, 20, a junior at Jackson State, said she thought this year would be her first “normal year” on campus before the water crisis wreaked havoc on the city.

Usher’s freshman year started in 2020 when Covid-19 prompted universities across the country to move classes online. Usher was one of the few freshmen students who decided to live on campus, she recounted. During her second semester in February 2021, a winter storm froze and burst pipes, leaving many city residents and university students without water for at least a month.

Unlike Washington who was able to go home to Chicago, Usher has to stay on campus because she’s a member of the school band.

Usher moved into her dorm August 19 and even then, she said water was an issue. “Water from the faucets were running thin,” she said.

“A lot of people are packing up and leaving, the parking lots are empty.” She said. If she wasn’t required to stay, Usher says she probably would’ve made the trek home to Atlanta.

“We practice for six to seven hours a day and then how are we supposed to shower?” Usher said. She also has an emotional support bunny she has to make sure has plenty of water, in addition to herself.

Usher said she’s had to pour bottles of water in her trash can to shower outside due to the water pressure issue on campus, a situation she called “horrible.”

‘I thought this would be my first normal year’

Trenity Usher, 20, a junior at Jackson State, said she thought this year would be her first “normal year” on campus before the water crisis wreaked havoc on the city.

Usher’s freshman year started in 2020 when Covid-19 prompted universities across the country to move classes online. Usher was one of the few freshmen students who decided to live on campus, she recounted. During her second semester in February 2021, a winter storm froze and burst pipes, leaving many city residents and university students without water for at least a month.

Unlike Washington who was able to go home to Chicago, Usher has to stay on campus because she’s a member of the school band.

Usher moved into her dorm August 19 and even then, she said water was an issue. “Water from the faucets were running thin,” she said.

“A lot of people are packing up and leaving, the parking lots are empty.” She said. If she wasn’t required to stay, Usher says she probably would’ve made the trek home to Atlanta.

“We practice for six to seven hours a day and then how are we supposed to shower?” Usher said. She also has an emotional support bunny she has to make sure has plenty of water, in addition to herself.

Usher said she’s had to pour bottles of water in her trash can to shower outside due to the water pressure issue on campus, a situation she called “horrible.”

Jaylyn Clarke, 18, a freshman, had been on campus for a week before the floods. She took the opportunity to get to know the campus and meet new people. Clarke was looking forward to the experience of attending a historically Black university and enjoyed the perks of staying close to home, which is only three hours away in New Orleans.

Clarke started to see river flood warnings last Thursday, which made her nervous about the potential for flooded roads nearby and being trapped on campus.

“Basically, we couldn’t do our laundry because of low water pressure, the showers and the toilets weren’t working well, and it even affected the AC,” she said, adding the water was brown and smelled like sewage.

Clarke finally decided to go home to New Orleans on August 30 to shower, wash clothes and attend online classes until the issue is resolved.

“I’m going with the flow because I do love Jackson State, but this water issue is like a rain cloud, like a shadow that’s being casted over.”