By David Squires

Fans and supporters – even in MLB suites – are celebrating the upstart National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) baseball programs at three historically Black colleges and universities, Dillard University and Philander Smith College of the Gulf Coast Athletic Conference and Wilberforce University of the Mid-South Conference.

This level of baseball – where some teams can’t even afford a tarp to protect their fields from rain — is the seedling planted by the baseball gods to help recruit and develop a new generation of U.S.-born Black baseball players.

The success and continued growth of these HBCU teams is critical this year, as the MLB began spending its $150 million, 10-year investment in diversifying the game. The plan was already in place before the announcement in October 2022 that the World Series would be played without U.S.-born Black baseball players for the first time in 72 years. That sobering news followed a season in which Opening Day rosters in 2022 included only 7.2% U.S.-born Black players, down from 18% in 1991, according to the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. That number dipped slightly, to 6.2% for Opening Day 2023, according to statistics MLB provided.

MLB chief baseball development officer Tony Reagins doesn’t have a magic number he wants to reach, but he believes the numbers will improve with programs MLB and the MLB Players Association (MLBPA) have implemented, and with new partnerships yet to be forged.

He noted four of the top five players drafted last year participated in MLB diversity programs, most of them since they were 13 or 14 years old.

“I get to see these kids year over year, and there are more of them,” Reagins said, “and they are getting better and better every year. … The opportunities are beginning to pay off.”

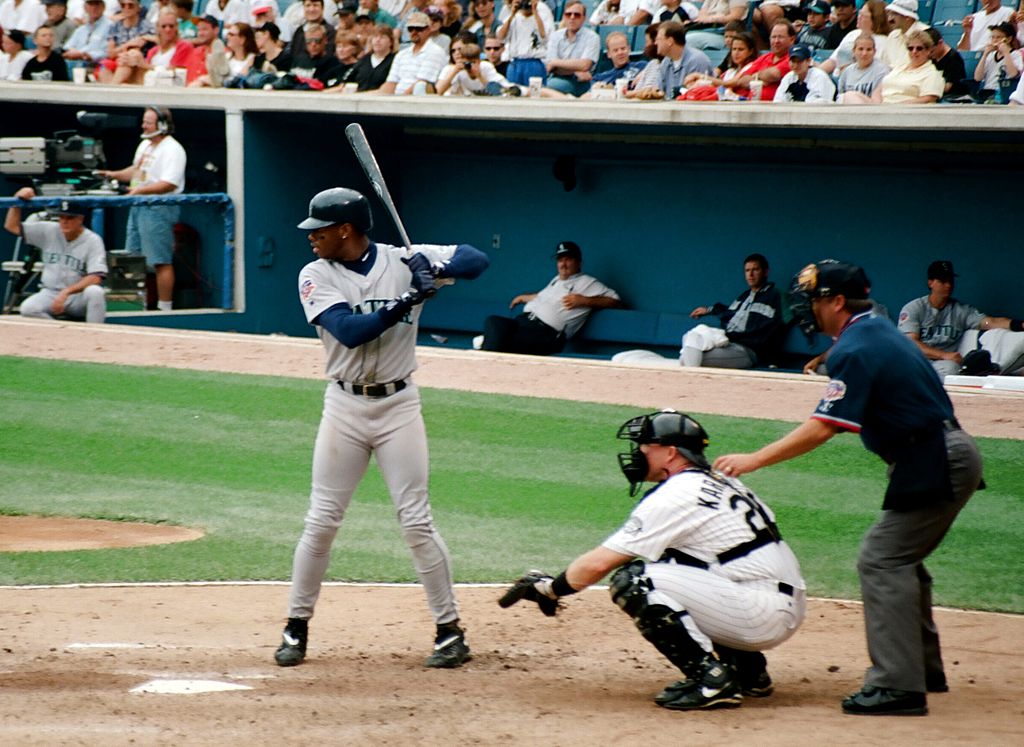

The inaugural HBCU Swingman Classic, scheduled for July 7 during MLB All-Star Week in Seattle, will feature 50 HBCU Division I players showcasing their talents. MLB, the Players Association and Ken Griffey Jr., an ambassador for the MLB-MLBPA Youth Development Foundation, announced the event in December. It will take place in T-Mobile Park, where Griffey played with the Mariners.

MLB’s role in the development of NAIA teams grew during the 2023 season. With U.S.-born Black baseball players already hard to find in Division I, even at HBCUs, it made sense to grow players at the NAIA level, where 80% to 90% of the players are U.S.-born and Black.

Those numbers describe the Dillard team, which is playing for its first championship, in its first season.

Dillard’s Bleu Devils earned their automatic bid to the NAIA regionals in late April by winning the inaugural Hope Credit Union GCAC Baseball Championship tournament, which was played at the Hank Aaron Sports Academy in Jackson, Mississippi.

Two other GCAC members, No. 1 Rust College and No. 3 Wiley College, played in the Black College World Series at Riverwalk Stadium in Montgomery, Alabama, last week, where NAIA bracket winner Florida Memorial University defeated NCAA Division II bracket winner Albany State 5-4 in a 19-inning marathon for the Black College National Championship. Riverwalk Stadium is home of the Tampa Bay Rays’ Double-A affiliate, the Montgomery Biscuits, and the MLB-MLBPA Youth Development Foundation served as the official game ball sponsor.

JOSHUA GIBSON

Dillard freshman left fielder Emmanuel Taveras and his teammates were undeterred after being left out of the BCWS. They had bigger plans: pursuing an NAIA national championship.

“We were instilled that we were brought here to make history,” said Tavares, who grew up in New Orleans playing travel ball with teams such as the NOLA Baseball Club and LTG (Love the Game). “It doesn’t matter that it was our first year.”

Dillard’s season earned GCAC coach of the year honors for Grant and pitcher of the year for Dallas native Jorge Guerra, who also was named the first team all-GCAC starting pitcher. Reliever Dylan Scott and third baseman Jalen Ayers also made first team all-conference.

One big help for the Bleu Devils is that they play home games at the MLB New Orleans Youth Academy (Wesley Barrow Stadium), about 10 minutes from Dillard’s campus and even closer to Southern University New Orleans, which will start playing baseball next season. The stadium is also the home field for Xavier University, which restarted baseball in the NAIA Red River Conference in 2021 after a 61-year absence.

At the academy, Grant and his players also get a practice field and coaching assistance.

J’BRIONNE HELAIRE/DILLARD UNIVERSITY

Reagins and Eddie Davis, director of the New Orleans Youth Academy, said the league already had seen the start of an MLB-HBCU relationship by nurturing players through the academy, Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities and other youth initiatives and by continuing to develop them through college baseball.

“What we found in New Orleans is that a lot of the players who have gone through our programs have gone to these colleges,” Reagins said. “Dillard didn’t have a program, and Xavier was struggling.”

Davis said he had to convince Xavier officials, who were concerned there were not enough New Orleans youths available to support baseball, that their program could be seeded by players from MLB youth programs in cities such as Houston, Cincinnati, Chicago, Dallas, Detroit and other areas.

“This is something that was very deliberate,” Davis said. “It not only benefits the schools, it benefits us, too.”

Grant said despite diversity initiatives such as RBI, Black baseball player growth and development continues to be stymied by peewee and high school football coaches luring away the best athletes.

He also said money is not available for youth baseball coaches and “that time has gone and passed where guys wanted to volunteer” to coach neighborhood baseball.

“People are very busy now,” Grant said. “That’s what’s missing — those African American youth coaches that you had back in the day.”

Jean Lee Batrus, executive director of the joint Youth Development Foundation, said communities, municipalities and grassroots organizations can apply for a plethora of funds by connecting through the foundation’s website, baseballydf.com.

Alvin Franklin, director of revenue for the GCAC, hopes to connect with MLB-MLBPA officials to seek assistance for teams that don’t have long-term or geographic connections to pro baseball.

“Most of those [GCAC] teams still play on dirt fields,” Franklin said.

J’BRIONNE HELAIRE/DILLARD UNIVERSITY

Those teams include Philander Smith, another GCAC team celebrating after a year of baseball. The college, founded in 1877 in Little Rock, Arkansas, brought the sport back after a 45-year absence.

Though the Panthers finished fourth in the GCAC, the team’s biggest feat was simply getting on the field.

Coach Noah Suarez, who was hired in late August, signed 21 players in 14 days, from Pakistan, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Utah, Florida and Maryland.

One of the team’s accomplishments was “just winning Game 1,” he said.

“We are giving opportunities to all different sorts of kids, regardless of their backgrounds,” Suarez said.

Suarez said teams at the NAIA level provide opportunities to minority players who might want to continue playing baseball, as well as for those who want to go into coaching, work in front offices or “go into the business field.”

“Since day one, when we had our first team meeting, the kids know I’m trying to help them wherever they need to go,” Suarez said, “whether it’s baseball or the real world.”

Another GCAC team that started playing baseball this year had a rough time: Oakwood University in Huntsville, Alabama, went winless in its inaugural season.

Franklin, the GCAC’s revenue director, said such growing pains are inevitable as the league reshapes itself as an HBCU conference.

“We are in the infant stages,” Franklin said. “There is a huge funding issue.”

Franklin said most GCAC schools’ athletic budgets are less than $1 million, adding that some schools cannot even afford a $3,000 tarp to protect their fields from rain, forcing the cancellation of some games. The league dodged a bullet during its recent tournament at the Hank Aaron Sports Academy, experiencing only a two-hour rain and lightning delay the day before the conference championship.

The schools’ major commodity, though, is U.S.-born Black baseball players, who are in high demand.

“Tougaloo [College] has 24 of 29 kids that are Mississippi kids, all Black,” Franklin said.

The University of the Virgin Islands, the only historically Black college outside of the continental United States, also will join the conference in the fall with a baseball team.

If Franklin needs guidance and support, perhaps he should look north to Ohio, where Wilberforce University revived its baseball program after an 80-year absence with a big assist from MLB’s Cincinnati Reds, just an hour away.

The athletics staff and players did not let a 5-36 record dampen the excitement of a six-year journey – delayed by the coronavirus pandemic – to field a team.

JANICE SMITH

Grade issues and stalled player transfers thwarted Wilberforce’s efforts to field the talent it desired.

“We just fought hard to do what we needed to do to finish the season,” said freshman second baseman Joe Mendy, who played in the Reds’ Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities program for three years before playing in college.

“I played with the most amount of Black players ever,” Mendy said. “On previous teams, I was the only Black player. It’s good to play around your brothers.”

The Wilberforce team is coached by Roosevelt Barnes, a Reds scout who is also the Reds’ RBI coach. His current players are all U.S. born, including three white players. The Bulldogs, who play in the Mid-South Conference, have players from RBI programs in Cincinnati, Chicago and Detroit. Barnes said RBI players from Tampa, Florida, will join his next freshman class.

“We try to represent everything that [RBI founder] John Young stands for,” Barnes said. “We’re committed to making sure we provide opportunities for kids of color to be able to play this game, and we are thankful for kids to be able to come to HBCUs to play this game. I believe that’s a strategy we can win with.”

He said other HBCUs have contacted him about his “blueprint,” as have predominantly white institutions.

“We didn’t have the record we wanted this year, but we were a young team, and we’ll get better next year,” he added.

The Reds’ support to Wilberforce players extends beyond the playing field, with five players working in paid internships this summer through the parent ballclub.

Barnes, who has owned a real estate company for 25 years and has worked in asset management, said the origin of the relationship was a 10-year financial statement he presented to Reds leadership. Wilberforce’s athletic director, Derek Williams, presented it to the university’s board of directors, and the rest is history.

Jerome Wright, director of the Reds Urban Youth Academy, said more programs like the Wilberforce model are needed, particularly with less than 5% U.S.-born Black players in the college game.

Wright said the work can and will be done through the baseball academies already set up in cities such as Compton, California; Kansas City, Missouri; New Orleans; Houston; Philadelphia; Cincinnati; and Washington.

While no other program is as solidly linked to an HBCU as the Reds-Wilberforce partnership is, the New Orleans Youth Academy is renowned for its work with Dillard and Xavier, he added.

“It’s bigger than baseball,” Wright said. “Opportunities like Wilberforce are helping to break that cycle.”