by Adam Wren

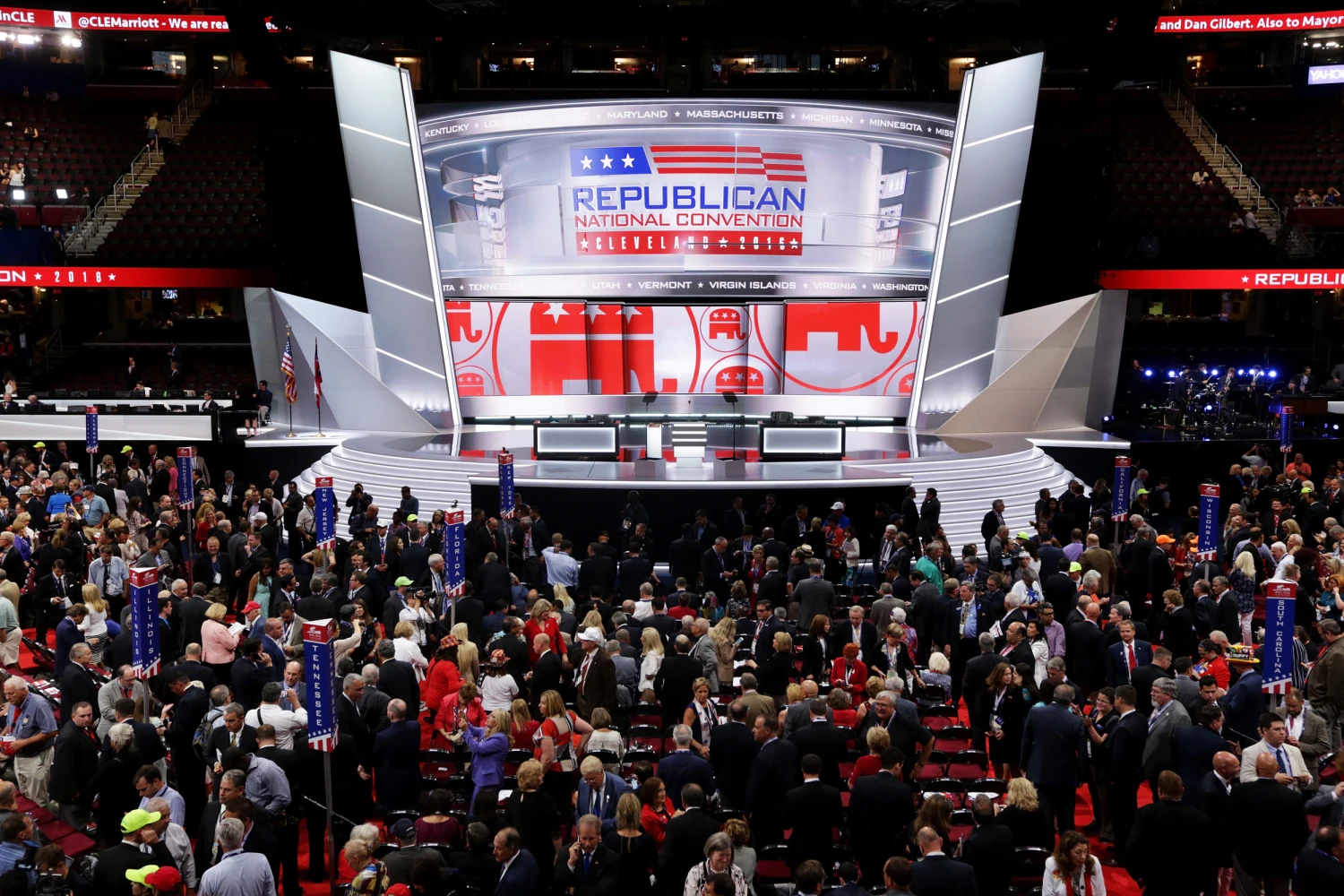

A new kind of Republican Party is revealing itself at its national convention.

All the markers of a MAGA jamboree are on display, from hulking Donald Trump iconography inside the convention hall to rhinestone Trump cowboy hats and red Trump-Vance placards.

But look closer and the party is changing — increasingly embracing economic populism at home and isolationism abroad, shifting its decades-long position on abortion and not only leery of, but hostile to, certain business interests.

Trump’s newly-announced running mate, Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio, has said that the GOP is in a “late Republican period,” and the party needs to “get pretty wild, and pretty far out there.”

And that’s exactly what’s unfolding in Milwaukee. It wasn’t just Trump’s selection of Vance, the opponent of Ukraine aid who once said “I don’t really care what happens to Ukraine one way or another.” It was also the party’s adoption of a slimmed down abortion platform and the criticisms of corporations it heard on the RNC floor.

It’s the result of a confluence of economic, demographic and cultural changes — including a newly ascendant labor movement, which the GOP finds itself increasingly attracted to, at least nominally. Together, those forces have only accelerated the GOP’s flirtation with a renovation of the party.

“I think what we’re witnessing now is a full on frontal assault on conservatism,” said Marc Short, who served as chief of staff to Vice President Mike Pence from 2019 to 2021, who is so estranged from this new version of the party that he was advised to skip the convention. “And you can look at the platform walking away from issues like life and traditional marriage, embracing tariffs across the board, but I feel like yesterday and last night went a step further when you have speakers that are basically saying NATO was at fault for Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and referring to job creators as ‘corporate pigs’ and announcing national right to work.”

He said, “That’s an enormous departure from where our party has been and I don’t think it’s a prescription for success.”

Perhaps most shocking to some more traditionalist Republicans was the fiery speech from International Brotherhood of Teamsters President Sean O’Brien — the first Teamster to speak at an RNC in its 121-year history. In his remarks, he trespassed on traditional economic conservatism, decrying the “corporate elite,” outlining the harm of Right to Work laws, which make it harder to organize and have been passed mostly in GOP-run states, and called the Chamber of Commerce “unions for big business.”

David Urban, the former 2016 Trump campaign adviser, told POLITICO he looked at his CNN co-host David Axelrod, the former Barack Obama adviser, and asked him while off air: “Am I at the right convention?”

O’Brien’s remarks left some watching — in the hall and from afar — nearly physically uncomfortable, even as they slowly began to embrace a new brand of Republican base voter.

“I was starting to squirm a little bit on some of that stuff, but I also know how you blend that, and that’s what makes up my support,” said Sen. Mike Braun of Indiana, who is running for governor and is one of the wealthiest members of Congress. “And that doesn’t mean you take the most outrageous stuff that he might have said, but you don’t dismiss some of the rest of it, and you find a new coalition.”

Or, as Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio put it: “I think President Trump has made our party what it always should have been, which is a populist party rooted in conservative principles.”

For years, the GOP has been undergoing a sea change as a working class party — all revolving around the organizing principle of America First. At times during his presidency, Trump reverted to more traditionalist GOP ideology on issues including tax cuts, which he cut in 2017. But it was his selection of Vance that could ultimately cement the party’s trajectory toward a different point on the horizon.

“Vance was the most distinctive choice he could make, in part to send a signal: I think coverage has rightly captured what we are certainly hearing which is that the business community and Wall Street and so forth, are, are deeply dismayed and concerned — as they should be,” said Oren Cass, a former economic adviser to Mitt Romney’s 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns, and a close associate of Vance’s who spoke with him last week.

In the coming years, Cass, the founder of the conservative think tank American Compass, a group aimed at developing a new center-right consensus on policy, predicted “a multi-ethnic, working-class conservatism as the foundation of an actual Republican Party that could achieve a durable governing majority.”

In Milwaukee, there have been vestiges of the old party in view, too. Nikki Haley, who championed a Reaganesque policy agenda during her presidential campaign received a smattering of boos as she strode on stage to speak on Tuesday night, even as Trump himself applauded.

“We must not only be a unified party, we must also expand our party,” Haley said. “We are so much better when we are bigger. We are stronger when we welcome people into our party, when we have different backgrounds and experiences.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who ran to Trump’s right in the primary, also received boos. The reaction to both Haley and DeSantis showed that, even though both candidates critiqued Trump from different vantage points on policy, it’s Trump’s personality — not his policies — that most endears him to the base. And Trump and his allies are coaxing the Republican Party away from the old party orthodoxy even more than during his first term — at least, quite literally, on paper.

The new GOP platform is the best example of this. The platform is now missing any mention of marriage being between one man and one woman, a longtime staple of party principles. Instead, it talks about promoting “a culture that values the sanctity of marriage” and “the foundational role of families,” in what has been largely hailed as a victory for pro-LGBTQ+ Republicans but a blow to the party’s socially conservative wing.

“This is a British Tory platform,” said former Sen. Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania. “This is not a conservative platform. Trump is aiming right down the middle.”

And then there is the matter of abortion. A contingent of anti-abortion delegates, citing the need to come together in the wake of the assassination attempt on Trump, dropped their fight against changes to the party platform that they argued backtracks on decades of GOP progress on the issue.

And most anti-abortion organizations have lined up behind the platform — largely because it mentions the 14th Amendment, which conservatives have long argued protects life beginning at conception. Still, the document reflects Trump’s leave-abortion-to-the-states approach in the post-Roe era, a position that leaves abortion broadly accessible in many states.

Delegates to the convention are largely embracing the former president’s view. Kip Christianson, a delegate from Minnesota who sat on the platform committee, described himself as “pro-life” but acknowledges that’s not the position of his state, where abortion is legal until a fetus is viable.

“This platform is a platform that is responsive and supportive of where America is actually at and where states like Minnesota are actually at. That’s all this is,” Christianson said.

He was milling outside of the convention center Tuesday, where the evening programming was just kicking off.

“We’re a big tent party,” he said.