By Bryan Mcclure

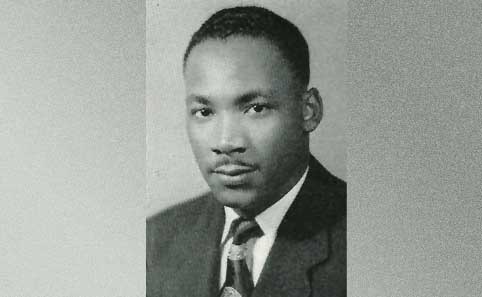

Ask any knowledgeable person the most famous graduate to come from a Historically Black College and nine out of ten times the first person they will say is Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a 1948 graduate of Morehouse. The long standing tradition of Morehouse, along with the fact that Blacks had very few options of schools to choose from during that era, landed the best and brightest African American males at that institution, including Dr. King. Beginning with Dr. King’s grandfather, the Morehouse legacy is strong amongst the King clan:

Dr. Adam Daniel Williams, grandfather, class of 1898 Atlanta Baptist College

Dr. Martin Luther King Sr., father, class of 1930

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., class of 1948

The Rev. A. D. Williams King, brother, class of 1959

Martin Luther King III, son, class of 1979

Dexter Scott King, son, attended 1979-1984

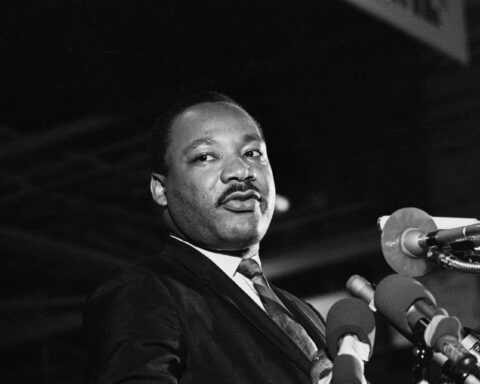

Michael Eric Dyson once wrote, “After all, without King, Morehouse’s national reputation and global fame would be considerably diminished. “Although there is surmountable truth in these words, they simultaneously symbolize an even more pressing and problematic concern the legacy of Black Colleges and successful men and women who come out of them. Like Dyson, so many people hastingly glorify the “great man” while decentralizing the institutions and environments that made them great. As is true in the case of Dr. King and Morehouse.

The truth of the matter is that without Morehouse and so many other Historically Black serving institutions there would have been no Dr. King. This is true for so many different reasons, but two factors are elements I directly experienced and relate to while I attended a HBCU. HBCUs have always been a place where “average” students are accepted and given an opportunity to matriculate while more attention is given to their needs. Secondly, more so than other institutions, (historically at least) HBCUs have been more aligned with serving the community and being socially conscience. At Morehouse, the “extra” time given to young M.L (as he was called during those days) allowed him to adjust to vigorous academic training while also combining the intellectual stimulation with community engagement.

In 1944, as enrollment numbers dwindled due to World War II, M.L then only fifteen years of age was given the opportunity to forego his senior year of high school and enter Morehouse College. By this time recently elected President Benjamin Mays had begun building upon the foundation established by John Hope. Under Mays’ leadership, he introduced what would become the standard Morehouse ideology, the “Morehouse Mystique,” a set of institutional principals emphasizing character building, cultural development and intellectual stimulation. Students were assigned faculty mentors, academic support and career guidance, Dr. King benefited immensely from them all.

King described Mays as “one of the great influences in my life.” While studying sociology, a young M. L. was also heavily influenced by premier Black professors. Men like department chair of the sociology program, Walter P. Chivers, George D. Kelsey, director of the School of Religion, and Samuel W. Williams, who introduced M. L. to Henry David Thoreau’s “Essay on Civil Disobedience.” Thus it was in those small intimate classes at Morehouse where Dr. King was heavily impressed with the idea of “refusing to cooperate with an evil system.”

Although young M. L. was captivated by his academic discourse and classroom discussion, his transcript reflects his struggle with “book learning.” Records show he did not earn his first A until his junior year in 1946-47 school year, in a Bible class with Professor Kelsey. It was in Professor Kelsey’s class where M. L. learned the implications of the Christian gospel and their uses for social and racial reform. King became the president of the sociology club, a member of the debate team, student council, glee club, ministers union, the Morehouse chapter of the NAACP, and also stayed active by joining the Butler Street YMCA basketball team.

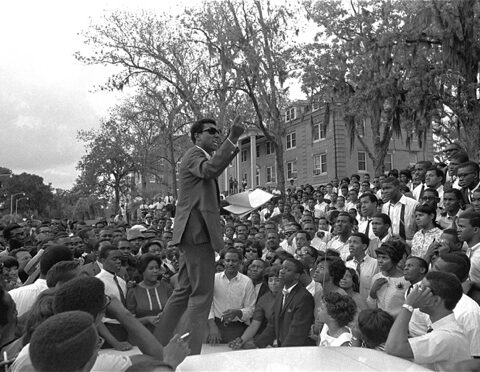

By young M. L.’s junior year, he was already transforming into the King that we know today. The summer of his junior year at Morehouse, he wrote a letter to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution declaring, “We want and are entitled to the basic rights and opportunities of American citizens.”

A year later he reminded his fellow Tigers in a letter to the Maroon Tiger what a true education meant. He wrote:

“We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character that is the goal of true education. The complete education gives one not only power of concentration but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate. The broad education will, therefore, transmit to one not only the accumulated knowledge of the race but also the accumulated experience of social living.

If we are no careful, our colleges will produce a group of close-minded, unscientific, illogical propagandists, consumed with immoral acts. Be careful, “brethren!” Be careful, teachers!” Certainly, King had an unparalleled impact and influence on the legacy of Morehouse. However, it is equally as important, quite possibly more important that we never forget how these institutions shaped our leaders.